Some claim that this is not a tax because of definitional difficulties, yet it seems appropriate to term it a tax when government action transfers wealth from a group of people to themselves.

I received an interesting follow up question from Heath B. He says,

“This is a follow up question for the post you wrote about ‘Why Does the Federal Reserve Target 2% Inflation?’

Milton Friedman once stated that, ‘Inflation is taxation without legislation.’ Are you able to give your insight into that claim? If that is correct then why do we as American citizens allow that to happen? One of the reasons we fought the revolutionary war was because of taxation without representation.”

Both parts of Heath’s question interest me. The short answer is yes, Friedman is correct. But how does the inflation tax work, and, in Heath’s words, why do we put up with it?

The Inflation Tax

What makes inflation a tax then? We should discuss how the government can spend money at all in order to understand, I suppose. You and I are not like the government. By manufacturing things and services and reselling them at prices that both parties agree upon, it does not make money.

Instead, there are essentially three ways for the government to raise money for spending. Taxes, borrowing, and money printing are all ways it can get cash.

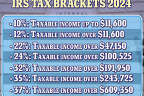

Since we all pay taxes, it is the easiest of them to comprehend. When you make money, spend money, have a relative pass away, possess property, or actually do much of anything, the government assesses you a fee. You can either pay the fine or risk receiving a higher fine and jail time.

The government may also take out a loan. The government sells a financial instrument known as a bond to do this. The person or entity purchasing the bond provides the government money today in exchange for a future guarantee from the government to repay them with more money (principal + interest). This is where the annual deficits and the actual national debt originate.

Last but not least, when a government utilizes paper money, it can simply print more to spend. In practice, the process used by the US government to accomplish this is a little bit more muddled. Our government does not use newly produced money to pay its bills. Instead, using money that it creates out of thin air, the Federal Reserve purchases government bonds from private organizations (such as banks).

How does this generate income? To comprehend, picture yourself possessing this ability. Imagine having the ability to print your own money that could only be used to purchase government bonds. Do you want to do it? If you desired a lot of money and didn't mind hurting people in the process, you probably would. Recall that interest is paid on government debt. Therefore, when you purchase bonds using printed money, you are only exchanging your newly created funds for an asset that will generate income for you.

However, how does this increase government revenue if the government is the entity paying interest to the Federal Reserve? The Federal Reserve has typically returned interest to the U.S. Treasury after deducting some expenses.

To put it another way, the Treasury obtained a loan (issued a bond), the Federal Reserve purchased the bond from the party who provided the government with a loan, and the Federal Reserve returned to the Treasury all of the interest due on the loan. This amounts to something akin to a loan that the government was able to make to itself at no interest, and it is only conceivable due of the Federal Reserve's manufacture of new money.

However, this is the creation of money; what about inflation? Well, the creation of new money and inflation go hand in hand. Any time you expand the supply of a good, the price of that good will fall in comparison to when you didn't. A considerably higher rate of price inflation results from the creation of money. It is for this reason that Milton Friedman stated that price inflation is "always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon."

As a result, when a bank sells a bond back to the Federal Reserve, it gets freshly minted money. As this fresh money is spent, the costs of goods and services grow along the route. (Dan Sanchez's piece, which explains this in more depth, is good.)

Since the nominal balances remain unchanged as inflation increases, the real cost of debt decreases, further assisting the government. Additionally, the United States government is itself a debtor, as is common knowledge.

The outcome is obvious. The amount of money available to the government is higher than it would be without money creation. Additionally, funds held in U.S. dollars by Americans (or anybody else for that matter) are depleted when inflation soars. This is a wealth transfer from savers to the American government.

Some claim that this is not a tax because of definitional difficulties, yet it seems appropriate to term it a tax when government action transfers wealth from a group of people to themselves. I therefore consider inflation to be a tax inasmuch as it results from an increase in the money supply.

They Can’t Keep Getting Away With It?

Now for Heath's second query: How can American taxpayers permit the government to get away with this? It's critical to emphasize that various parties gain from the creation of money in order to provide a response.

Keep in mind that the bonds the Federal Reserve purchases come from private companies. These private companies offer the bonds at a price they think will make them money; otherwise, they wouldn't sell them at all. The company receives freshly printed money when they sell the bonds. Since that money is just now entering the market, prices haven't yet increased as a result.

To put it another way, the first person to get new money does so before inflation reduces its purchase value. Getting new money first has a benefit. This is known as the Cantillon effect in economics.

Who gets the fresh cash first? Big financial entities like banks are frequently involved. For their part, banks are well-organized and are aware of the advantages of receiving additional funds. Therefore, we should anticipate that they are prepared to spend money to ensure that Federal Reserve policy is advantageous to them.

Who, on the other side, suffers from inflation? The expenditures are, in fact, shared among the millions of people who possess US dollars. We would anticipate that if the expense is shared among such a huge, disorganized population, it would be too expensive for any one person to justify their time in opposing this kind of policy.

This exemplifies the logic of collective action, as defined by economist Mancur Olson. It is simpler for the small group to mobilize in support of the policy since the benefits are concentrated on one small group and the disadvantages are distributed over one large group.

Louis Rouanet and Peter Hazlett, two economists, point out instances in which it appears special interest groups were successful in influencing central bank policy for their personal gain at the expense of society. They provide evidence for this in the cases of the Federal Reserve's responses to the COVID outbreak, the 2007 financial crisis, and the evolution of the Euro.

And even though the Federal Reserve's approach may differ from the general explanation given above in these specific situations, Rouanet and Hazlett's main conclusion remains the same. To the expense of everyone else, the Federal Reserve can appease specific interest groups by using its mechanism for creating money.