A lot of new information about a draft multilateral tax deal was made public by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) last week. The dump of documents has to do with OECD Pillar 1, Amount A, which is a plan to change where big multinational businesses pay taxes on their profits.

At the moment, businesses usually pay taxes on their income in the places where they make their products. When you have a factory and employees in a country, you have to pay taxes on the money you make from those actions. In addition, if you have intellectual property that makes a lot of money in one place and sales and distribution that makes a lot of money in another, your taxable profits should match the profits you make.

Pillar One is based on production. Amount A, on the other hand, would send a portion of profits from the places where the biggest companies are taxed now to the places where their final customers are located. This is done by rules that tell businesses they have to do their best to find out where the people who buy their goods are. People expect businesses to know (as much as they can) where their products are bought by customers, even if they are selling a secondary good to another business.

Here are five important things you should remember from the new papers.

1. The draft treaty presents a path to removing (at least some) digital services taxes.

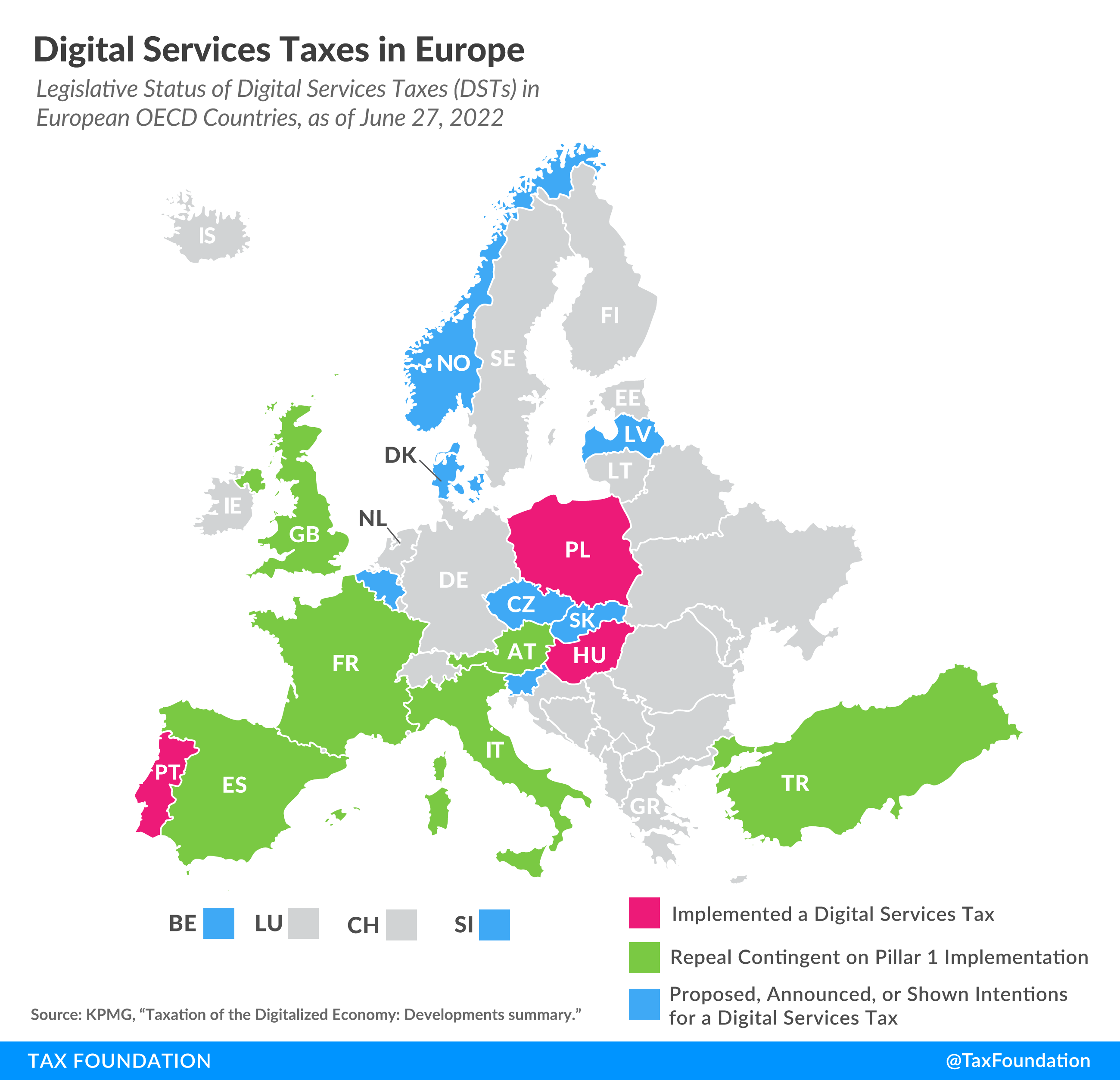

Countries have been putting in place new laws that tax companies that offer digital services over the last few years. It's not good that these digital services taxes (DSTs) are passed. For starters, they are unfair. One usual approach is to set the revenue threshold so high that most of the businesses that have to pay the tax are foreign ones. The rules are also specific to certain types of businesses, like those that offer online streaming services, digital ads, or the sale of user data. This goes against the neutrality concept.

Second, businesses are taxed on their gross sales instead of their income. That is, the tax will have to be paid even if a certain digital service isn't making money.

U.S. lawmakers have always been against these DSTs because most of the companies that will be affected are based in the U.S. Most recently, Senate Finance Chairman Sen. Ron Wyden (D-OR) and Ranking Member Sen. Crapo (R-ID) wrote a letter about Canada's proposed DST.

With a multilateral deal (more on this below) or trade threats and a possible trade war, one clear goal of U.S. policymakers has been to get rid of DSTs. After France introduced the DST, the Trump administration said it would put 25% taxes on $1.3 billion worth of trade with the EU in 2020. The start date for these taxes was pushed back, and they are still not in effect.

It took a long time for the OECD multilateral negotiations to lead to a draft multilateral treaty, but here we are.

One key element of the draft treaty is Annex A, where you will find a list of policies that will be removed once the treaty is adopted. Included in that list are the DSTs of eight countries. The list is not fully inclusive of all discriminatory digital tax policies. But the draft treaty also eliminates the allocation of taxable profits to countries that do not remove policies that fit within the draft treaty’s definition of DSTs and relevant similar measures (see here for the specific language):

The tax is driven by the location of customers or users. It is generally a tax on foreign businesses. It is not a tax on income and is beyond agreements to avoid double taxation.

The incentive to remove a DST other than those already specified will depend on whether a country sees a better tax revenue outcome from Pillar One, Amount A. In turn, those revenue numbers will depend on how the rest of Amount A gets negotiated.

Also, it seems unlikely that these principles will result in “all” DSTs being removed as agreed in October 2021. There is room for governments to work around the principles above. A DST could potentially get past the second principle by applying it to both domestic and foreign businesses in a somewhat balanced way.

2. The treaty will not be adopted without U.S. support.

The draft treaty proposes a points system to determine whether a critical mass of jurisdictions has agreed to the treaty. The entry into force provisions require 30 ratifications and approval by jurisdictions representing a total of 600 points or more. The points ascribed to jurisdictions can be found here. The United States has been assigned 486 points, and there are 999 points available. There is no path to 600 points without approval from the United States, and the U.S. Constitution requires 67 votes in the U.S. Senate to ratify a treaty. This appears to be a rather unlikely outcome at this juncture.

3. Not all countries agree.

For a few reasons, this is just a "draft" of a multilateral tax deal. One reason is that the U.S. Treasury wants people to have their say on it. Another reason is that a number of countries have said they don't agree with the draft plan.

Brazil, Colombia, and India don't agree with a few of the rules. One of them says that the current taxes that are in place in market countries should make it harder to tax the profits that are allocated under Amount A. It comes down to whether you want to double dip or not. If a country already has the power to tax a company on the work it does in that country through withholding taxes and Amount A would give that country new taxing rights, should the new rights be given on a gross or net basis? I believe that Amount A shouldn't add to the taxes that are already being collected in market areas.

India, Brazil, and Colombia all seem to think that the money should be given out in full, with no deductions for taxes already paid. Other countries seem to want a net allocation, which means that the Amount A taxing right is lessened by the taxing rights that are already in place in a market state.

4. This is truly a unique (and complex) tax policy.

Part One of the draft multilateral tax treaty would change who has the right to tax the biggest multinational companies' income. According to the OECD, the taxing authority over about $200 billion in profits would be moved to places other than those where the gains are taxed now. Based on figures from 2021, the changes would cause taxes to go up by between $17 and $32 billion because each jurisdiction has a different tax system. The OECD says in their report that their research shows that low- and middle-income countries will get more money from taxes while tax havens will lose most of it.

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has said in the past that it is hard to say what will happen to U.S. income because there are still disagreements about the treaty text.

Businesses that make more than $200 billion in profits will have to follow new rules because of the plan. These suggested rules say that 25% of profits above a 10% profit margin should be taken away. They use a number of calculations and rules to figure out where those profits should come from and where they should be taxed.

There are formulas for all sorts of things:

A formula for determining where a company gets relieved from taxation. A formula for allocating taxable revenues across jurisdictions. A formula for determining a taxable presence in a jurisdiction.

None of these approaches have truly been tested before in international tax policy, which is why last year my colleague and I wrote that the policy seems to be one “that works in theory and may have a slight chance to work in practice.”

5. Nobody knows what will happen next.

The U.S. Treasury has made the plan public for 60 days so that people can look it over and give their thoughts. Like everyone else in the U.S. tax world, we at Tax Foundation are taking this consultation very seriously.

But if the U.S. feedback process tells the Treasury that more changes need to be made, it's not clear if other countries will agree with those changes. It looks like Canada is moving forward with its DST, and the U.S. government may be threatening to raise tariffs again soon.