In June, the European Commission suggested a new source of revenue as part of its second basket of own resources: a 'temporary statistical own resource based on company profits.' This is an effort to help the EU's budget while it pays off its debt. Previous ideas for new EU own resources have focused on narrower tax bases, such as a financial transaction tax (FTT), digital levies (DSTs), or taxes on crypto activities.

Technically, this proposal for "own resources" is not a tax, but it would force EU Member States to change their budgets (either by raising taxes or cutting spending) to pay the new amounts to the EU budget.

A possible contribution from the Business in Europe: Framework for Income Taxation (BEFIT) project is expected to replace the plan for a temporary measure. But what does the Commission really want to do? What does it mean for the long-term budget and own resources of the EU and its member states?

Understanding the Proposal

With this tax, Member States would have to send 0.5% of the gross operating surplus (GOS) from both financial and non-financial companies to the EU budget. The Commission thinks that this plan would bring in about 16 billion euros (in 2018 dollars) to help pay for the EU's long-term budget. According to the Commission, this is not a direct tax on companies, nor would it raise companies' compliance costs.At the moment, the European Union gets most of its money from customs duties, contributions based on the value-added tax (VAT) that Member States receive, and direct contributions from EU countries (called the "gross national income-based resource"). In 2021, the Union also put in place a contribution based on plastic packaging trash that was not recycled.

The biggest source of income for the budget is the GNI-based resource, which will be worth about EUR 116 billion in 2021 and make up about 70% of the Union's budget. About 13% of the Union's income, or about EUR 20 billion, comes from customs fees, while about 11%, or about EUR 15 billion, comes from VAT-based contributions. The "plastics own resource" brings in about 3 to 4 percent of the EU budget, or about 6 to 8 billion euros each year.

Compared to these resources, the new company own resource would not become the Union's biggest source of income, but at 16 billion euros, it would be the same as the VAT-based resource.

But the way the GOS payment works with the other ways the EU makes money is complicated. Because GOS is a big part of GNI, it is mostly just a matter of adding up the numbers twice. Even if this is just a temporary move, the Commission should be clear about how this works.

This measure adds to and updates the second basket of proposed new own resources, which follows the first basket proposed in December 2022. The first basket included revenues from the emissions trading system (ETS), the carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM), and the reallocation of multinationals' leftover profits under the OECD/G20 agreement on a re-allocation of taxing rights (Pillar One).

The idea behind the plan is to have a temporary measure to balance the basket of own resources and make the EU budget's income sources more diverse until BEFIT is officially proposed. Things ss Things Things Things Things. The g L... But Member States would still have to pay down the EU debt even if they didn't have a new own resource.

How Would Contributions Be Determined?

The plan from the Commission is based on the idea of gross operating surplus, which is the term used in national accounts for the total income from capital before the capital stock is depreciated. In reference to financial and non-financial corporations, GOS measures private sector company profits before depreciation.For European Union member states, GOS can be calculated from Eurostat national accounts data by taking gross value-added (GVA) and subtracting pay for workers, taxes, and net subsidies on production and imports.

To figure out what the EU's plan on corporate own resources might mean, it helps to look at past trends and possible contributions from Member States.

Historical Contribution to Own Resources

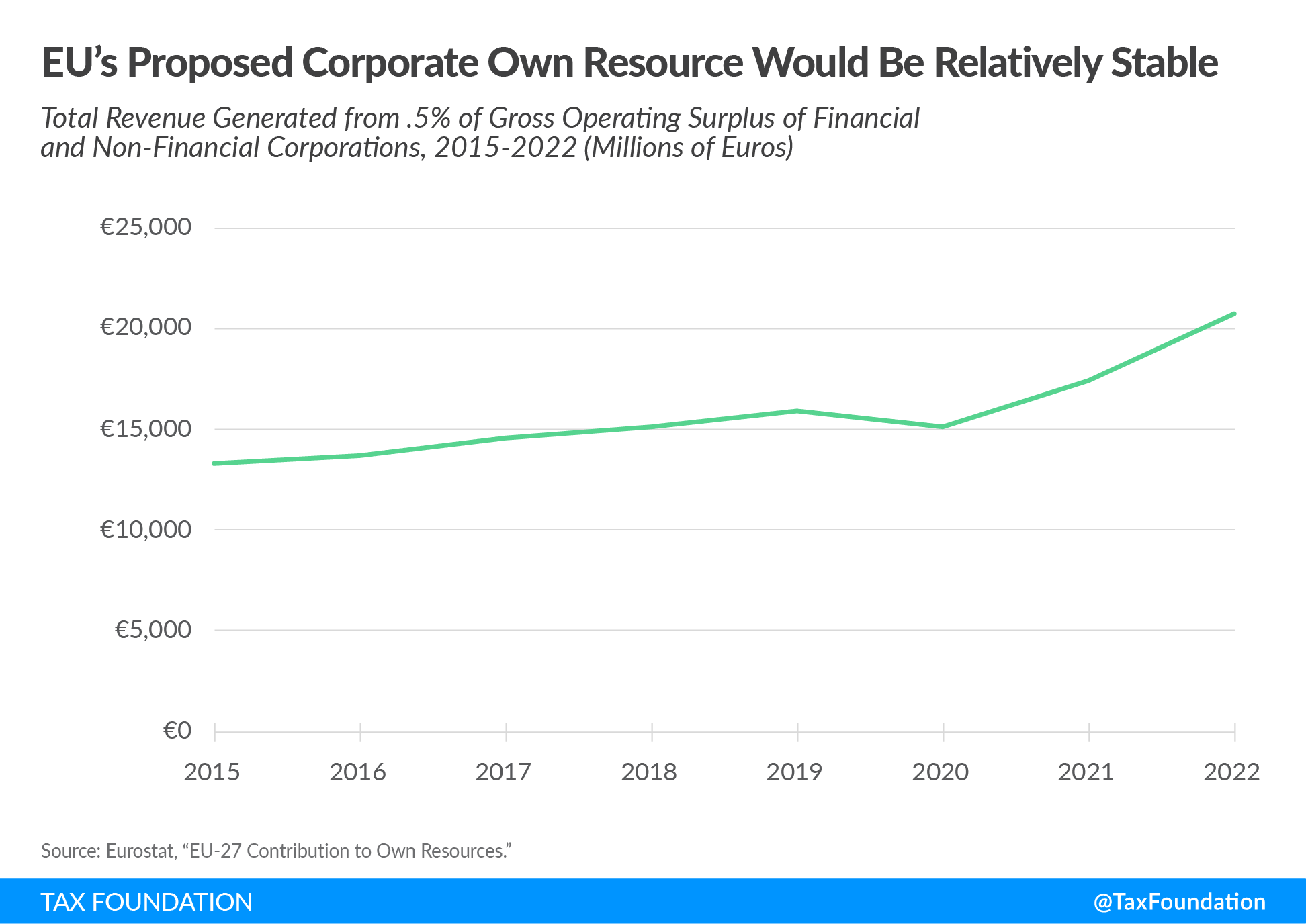

From 2015 to 2022, the total revenue that could have been raised from 0.5 percent of the gross operating surplus in the EU-27 demonstrates a relatively stable growth trend, despite a slight downturn in 2020.

What Would Member States’ Contributions Be?

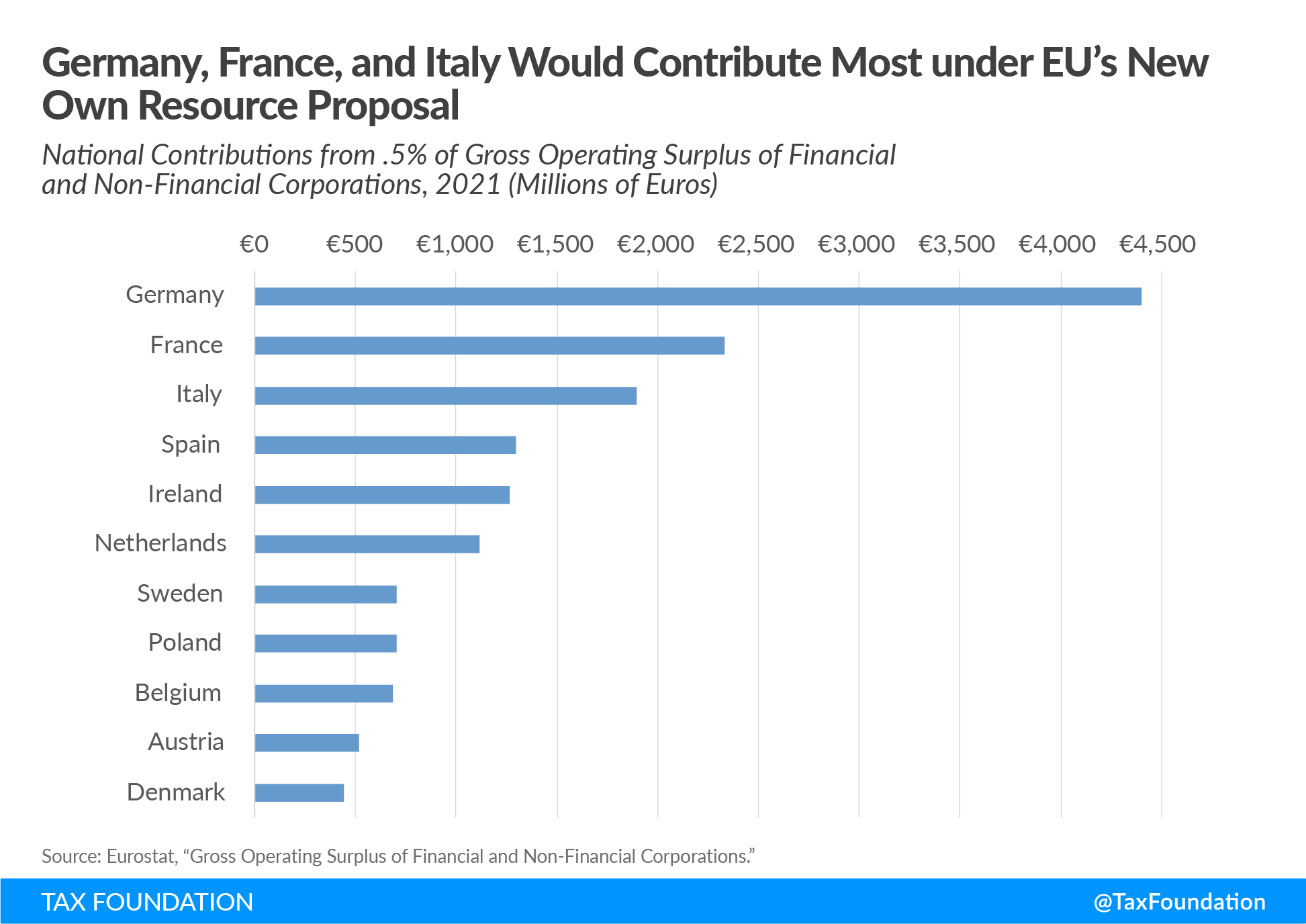

Based on calculations for 2021, we can compare individual Member States’ potential financial burden under this proposal.

Of the proposal’s expected EUR 17.44 billion in revenue, around 25 percent, or EUR 4.4 billion, would be contributed by Germany. France would contribute 2.3 billion, or 13 percent, and Italy would contribute 1.9 billion, or 11 percent. Overall, the national contributions collected by these three countries would make up half of the total expected revenue of the proposal.

Evaluating the Key Claims of the Proposal

It's true that the plan wouldn't directly cause any big changes to how the economy works. Since the corporate own resource wouldn't be a direct tax on businesses and would instead be collected as national contributions from Member States based on their gross operating surplus, it wouldn't change how economic decisions are made.Instead, Member States are responsible for funding their various national contributions and collecting the related tax revenue using existing national instruments. So, the amount of economic distortion caused by bringing in money relies on the tools that national policymakers choose. To keep this from happening as much, lawmakers could choose to cut national government spending or increase the tax base for value-added taxes (VATs).

Since Eurostat makes it easy to figure out the gross operating surplus of companies in EU Member States, the costs of complying with the measure will be cheap.

Overall, the Commission's plan for a company own resource is based on a simple and stable way to figure things out. Compared to some of the other ideas for new own resources, this proposal's revenue stability and effect on economic activity could make it a better choice. However, the real economic effects will depend on how Member States choose to pay for their share. As the Own Resources Decision moves forward, it will be important for policymakers to fully understand these processes.