So, recession it is, right? Not so fast.

Dear Capitolisters,

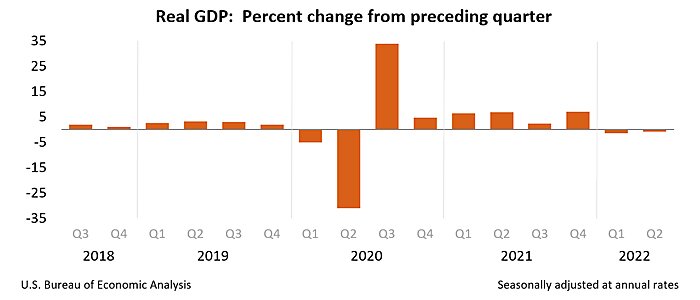

While I was (responsibly) drinking micheladas during the day last week, the internet exploded with a heated and mostly partisan debate about whether the country is now in a "recession" after the latest real (inflation-adjusted) gross domestic product numbers showed a second straight quarterly drop.

For Team Recession (primarily manned by the Republican/right), the argument was that two straight quarters of GDP contraction is, while imperfect, the longstanding shorthand for determining a recession—one that Democrats themselves have often used before doing so became politically uncomfortable. On the other hand, Team Not Recession (featuring mostly Democrats/lefties) countered that the “official definition” of a recession—traditionally assessed by Business Cycle Dating Committee of the academic National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER)—uses a wide range of economic data, including several indicators (most notably employment) that continue to show robust expansion. Both teams then yelled at each other for days; the White House held a big press conference; and folks even started fighting over the Wikipedia entry and related “fact‐checks”—as American political debates so often do these days (sigh).

That debate is, as we’ll discuss, honestly pretty silly. But it does offer a good opportunity to talk about recessions, the GDP calculation, the current state of the U.S. economy, and what policymakers should be focusing on right now.

(Spoiler: not the definition of “recession.”)

Who’s Right?

At the risk of upsetting everyone (but when has that ever stopped libertarians?), both teams have a point. For Team Recession, economic historian Phil Magness took to the Wall Street Journal to summarize the case for why the “two-quarters rule” should apply:

Economists have long defined a recession as “a period in which real GDP declines for at least two consecutive quarters,” to quote the popular economics textbook by Nobel laureates Paul Samuelson and William Nordhaus. This definition isn’t perfect, but it describes almost every downturn since World War II. …

There is no federal statute that appoints the NBER as the official arbiter of recessions. Quite the contrary, the federal government has historically followed the conventional textbook definition. The Gramm‐Rudman‐Hollings Act of 1985, which attempted to rein in the deficit by triggering mandatory sequestrations in federal agencies, introduced a recessionary escape clause for tough economic times. If the Congressional Budget Office projected a recession, Congress could fast‐track a vote to suspend the sequestrations. The law defined a recession as a period when “real economic growth is projected or estimated to be less than zero with respect to each of any two consecutive quarters.” The CBO could also trigger a suspension for “low growth” if the change in GDP dropped below 1% for two quarters.

Although the Gramm‐Rudman‐Hollings Act succumbed long ago to the profligate pressures of deficit spending, its “two consecutive quarters” standard may be the closest thing to an official definition of recession. Derivative language still appears in the federal statute books, and it has long been used as a basis for other counter‐recessionary measures governing federal employment. Canada and the U.K. also employ the two‐quarter definition to designate the onset of a technical recession, further attesting to its legitimacy.

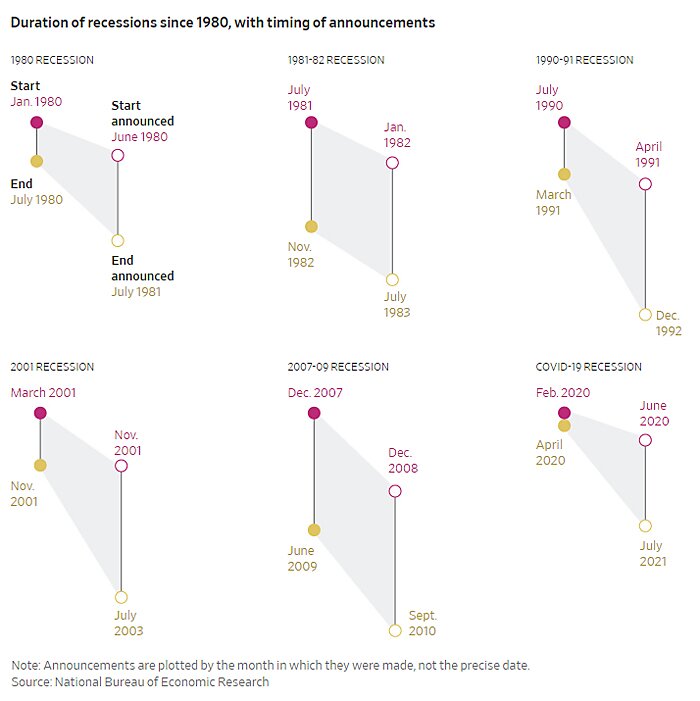

Magness adds, quite correctly, that the NBER approach “isn’t suitable for real‐time policy determinations” because it can take months for the committee to make its call, as this recent Wall Street Journal primer and accompanying chart helpfully demonstrate:

In short, there is no quick, easy, or official "definition" of a recession. However, two quarters of negative GDP growth is a pretty good shorthand that has been widely used in the past, including in economics textbooks and U.S. laws. Robert Barro, an economist at Harvard and AEI, made many of the same points earlier this week. And, of course, there are other economic signs that are also flashing red right now. Besides the still-bad inflation numbers, we also have terrible consumer sentiment, falling consumer confidence, flat real consumer spending, and an inverted "yield curve" (which plots the return on Treasury securities and goes negative during or right before a recession). And, as Eric Boehm of Reason points out, most Americans now think we're in a recession, which can lead to slower economic growth. So, we're in a recession, right?

Not so quickly.

Team Not Recession makes a lot of good points as well. But the Biden administration's claim that only the "official" call from the NBER is important is not one of them. (That's fine for school, but Magness and others are right that it takes months, so it can't be used to make policy decisions today or tomorrow.) Instead, their best argument is the current economic data, which includes, but is not limited to, the indicators that the NBER uses to (eventually) determine a recession:

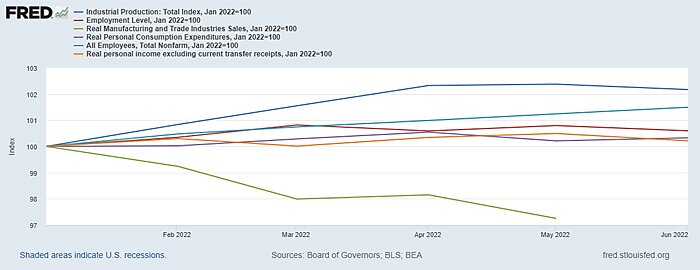

The chart above shows that, except for manufacturing and trade sales, all of the monthly measures of income, consumption, employment, sales, and production that NBER looks at are still above 100. This means that they were all higher at the end of June 2022 than they were at the beginning of the year. There are some red flags, but there are also some good ideas for growth.

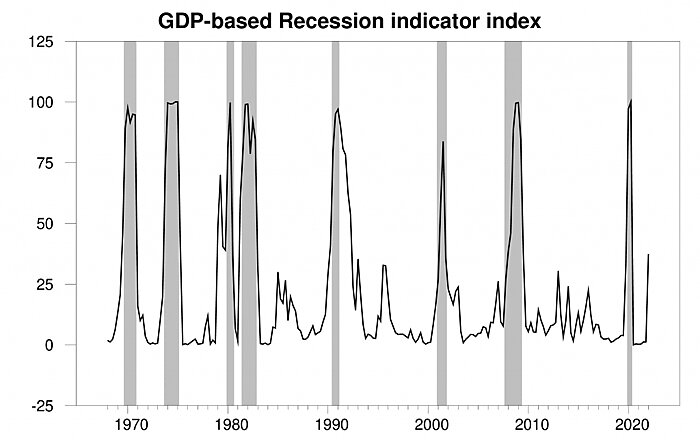

Other measures of economic activity say the same thing. For example, the people at Econbrowser have made a "recession indicator index" that is based on the same data that is used to figure out GDP. For the last 17 years, when the index goes above 65 percent, they have been able to correctly predict recessions. At the moment, it's only at 37.4 percent, but it's "flashing a clear warning sign":

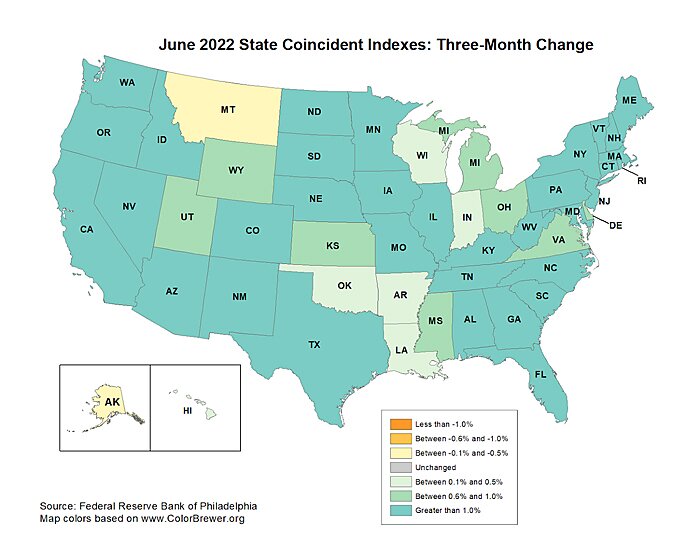

They also cite other positive data, such as the still steadily low unemployment rate (3.6 percent), still‐positive GDP growth over the last 12 months, and separate measures of national economic activity (“gross domestic output”) and state‐level activity (the Philadelphia Fed’s “coincident index”):

New data on manufacturing activity also show that growth has continued, though it is slowing down. This has never happened in a U.S. recession before. The team at Goldman Sachs also says that corporate financial results are still pretty good: "With nearly three-quarters of its market cap now reported, S&P 500 earnings are up 9% year-on-year, 52% of reporters beat consensus expectations by 1 standard deviation, and revenues are growing in every sector." …. The fundamentals of the credit market are also good news: defaults on high-yield bonds are well below average, let alone recession levels.

All of these are good signs that we're not in a recession yet, even though there are some headwinds.

I think, though, that the way GDP is calculated is probably the strongest argument against Team Recession's point of view. First of all, the first "advance" report on GDP, which just came out, is usually changed, and sometimes quite a bit:

Historically, GDP has been revised from positive to negative far more often (5 times in past 22 years) than a negative GDP report has been revised positive (1 time). pic.twitter.com/flr09A0hfg

— Jeffrey Kleintop (@JeffreyKleintop) July 28, 2022

This history might be especially important when dealing with a negative GDP print for the second quarter of just 0.9% and a very unusual "pandemic economy" that has caused a lot of changes to national economic data (because sampling techniques and seasonal adjustments weren't made for global pandemics). In fact, research from the San Francisco Fed in 2020 shows that when the economy is going through a rough patch, GDP revisions can be especially big. Maybe future changes to GDP data for the first and second quarters will show even bigger drops, but the historical imprecision of the preliminary numbers is still reason to be careful.

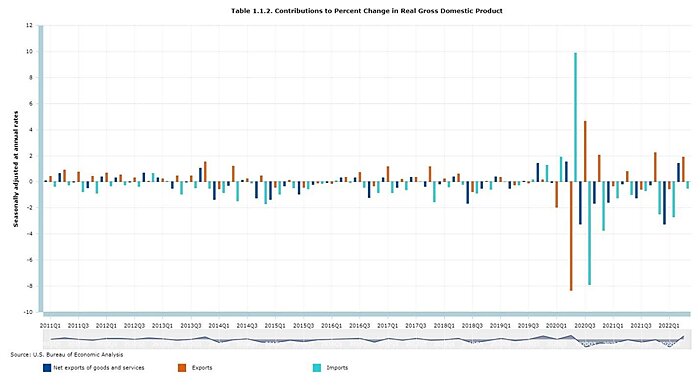

But how GDP is calculated is more important, and both the pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine have made this worse. In particular, GDP is a cumbersome sum of several economic indicators: private consumption plus gross private investment plus government investment plus government spending plus net exports (exports minus imports). Even when things are going well, this way of figuring out the U.S. economy can lead to wrong conclusions. In the past few years, economists have debated whether GDP measures real economic well-being or the large amount of economic activity that comes with "free" digital goods. And we at Cato have spent decades trying to explain (patiently, well, most of the time) that the mechanical "net exports" part of the GDP calculation doesn't mean that the trade deficit (also called "negative net exports") actually slows the growth of the U.S. economy.

Getting these numbers right has been especially hard in the last two years, when sudden changes here and abroad caused some parts of the GDP to swing wildly. For example, the first quarter's negative GDP number was caused by an unusually high "net exports" number. However, this number was mostly caused by the pandemic and not by a weak U.S. economy. In particular, the U.S. economy was much more active and open (and, as a result, ate up imports like there was no tomorrow) than most of the rest of the world, especially China, which was shut down, and Europe, which was suddenly falling apart. Because of this, U.S. imports went up while U.S. exports went down, giving us a record-high "net exports" number:

As the chart above shows, moreover, the pandemic has featured a lot of these wild trade swings, as compared to the previous decade. That volatility is a sure sign of economic uncertainty and pandemic‐related changes to the global economy, but it says little about whether we’re in a recession. (Indeed, as the chart above shows, imports usually collapse during recessions—see the big teal peaks in Spring/Summer 2020.)

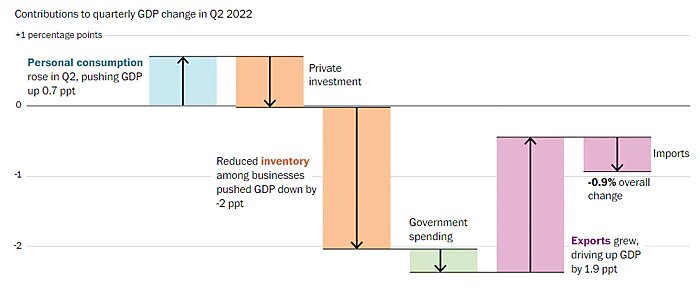

The second quarter featured similar irregularities with another volatile GDP component—inventories. In particular, a large reduction in U.S. companies’ inventories in the second quarter pulled down the “domestic investment” part of the GDP calculation:

But again, this was mostly about the pandemic: As the Delta variant (remember that?) raged and supply chains got better, U.S. companies built up huge inventories in the fourth quarter of 2021, which contributed to that quarter's surprisingly high GDP number. Since then, they've been drawing down these supplies, which drove the second quarter's negative number and also contributed to the first quarter's GDP drop. That isn't a clear sign of a weak economy. In fact, Ian Shephardson of Pantheon Macroeconomics pointed out last week that companies restocking for the fall could cause GDP to jump strongly in the third quarter.

In short, the two-quarters rule has worked in the past, but the pandemic and the Russian invasion seem to have made it less accurate this time. Goldman points out that the drop in GDP in the first two quarters of the year was caused by "the volatile imports and inventories." Some bad economy!

Who Cares?

As you may have guessed by now, I think Team Not Recession's policy arguments are better in general: There are problems with the U.S. economy, but there are still a lot of good signs, and some of them are still very strong (though others flashing warning signs). Given these problems with how GDP is calculated and the unclear origins of the two-quarters rule, it seems smart to hold off on all the "recession" talk (for now) and maybe even stop using that standard going forward.

But this whole argument is silly: Unlike "inflation" and other important economic terms, "recession" doesn't have an official definition—not in the law and not even at the NBER, which kind of just took on the role of "official recession arbiter" years ago. Key economic policymakers like Federal Reserve Chair Jay Powell are focused on the underlying economic data, not on whether a certain combination of data has magically unlocked a certain term that changes the course of the U.S. economy. I mean, it's not like white smoke starts coming out of the Eccles Building, Powell comes out and says, "Michael Scott-style," that we're in a recession, and then the U.S. changes its economic policy.

That would be pretty cool, I guess.

Of course, they should take the approach of the nerds: the fact that we were in a "technical recession" (or whatever) last quarter or are in one right now doesn't tell us much about what economic policy has done in the past or what it should do in the future. The data do show that, and right now, they are neither good nor bad, but they point in a bad direction for the future. And policymakers should just say that instead of spending days arguing about what "is" means.

Given all of these problems and the lack of clarity in the economic data, it's not surprising that most of the "recession" talk came from politics, where silly economic arguments not only exist but thrive, and where both parties are now getting ready for the midterm elections in November. I think they are looking in the wrong place for a few reasons. From a strategic point of view, both sides take unnecessary risks when they stick to their own definition of a recession. (What if GDP is changed or goes up a lot right before midterm elections? What if the NBER numbers get a lot worse? Etc etc.) Also, the White House's work has probably started the old Streisand Effect, which brings even more attention to the "recession" (and the Democrats' clumsy attempts to control the story).

Even worse, the debate has wasted a lot of time that could have been used to explain our messy reality to the American people and to come up with and implement real policies that might actually change the uncertain path of the U.S. economy. Most of the policy work, for better or worse, is done by the Fed right now. However, the White House and Congress could still pursue a few policies, mostly ones that loosen up the supply side of the economy and reduce uncertainty, to take some pressure off American consumers and businesses.

Unfortunately, Biden and congressional Democrats don’t really appear too interested in doing any of that stuff. In fact, the last week or so has seen even more near-term deficit spending (such as the $79 billion in chip subsidies that just passed Congress and the "frontloaded" "Inflation Reduction Act" that promises tens of billions more before any major tax revenues arrive), even more supply side restrictions (such as the "prevailing wage" rules tied to the chip subsidies or the IRA's plan to protect electric vehicles), and even more economic uncertainty (such as how the IRRA will affect the economy). No matter what the law is called, none of those things are good for a shaky and inflationary U.S. economy.

And that, not the "recession," is what's really wrong with the economy.

Chart(s) of the Week

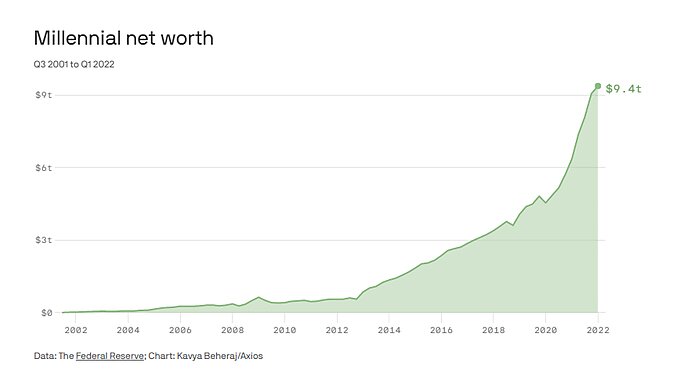

Millennials stopped buying avocado lattes or something

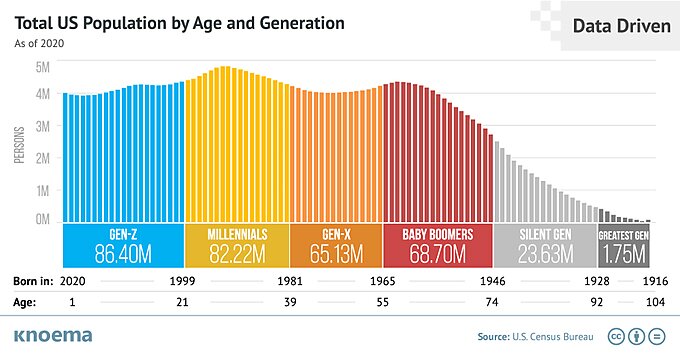

And there are a lot of them…

Not sure this meets the technical definition of a “chart,” but still cool…