The current federal budget deficit and the accumulated debt result from Congress spending more than they are willing to raise in taxes.

Congress spends more than they are ready to get in taxes, so the government has a budget deficit and a lot of debt. In the end, the answer to the question of which is more to blame—steady taxes or rising spending—will rely on our values: should the government use an ever-growing share of private resources, or should its growth be limited?

But the CBO's newly updated long-term budget outlook makes it clear that figuring out what will cause the future budget deficit is not a matter of moral judgment. Tax hikes can't stop the growth of spending on health care and retirement. Even if tax revenues stayed at the same level they were in 2000, when the US had a budget surplus, forecast deficits would still be higher than 9 percent of GDP by 2053. Tax cuts are not to blame for the growth in required spending, which is driven by things like population growth and the benefits formula.

This short piece will start by giving some background on U.S. fiscal trends and then talk about the two different problems with budgetary sustainability: the rate of growth of future spending and the amount of government spending that people want. No matter how much you want the government to spend or how much you want to pay in taxes, you have to fix the fact that federal spending is growing too fast to be sustainable. But if people don't cut back on spending, any tax relief will have to be temporary.

Spending Consistently Outstrips Revenue

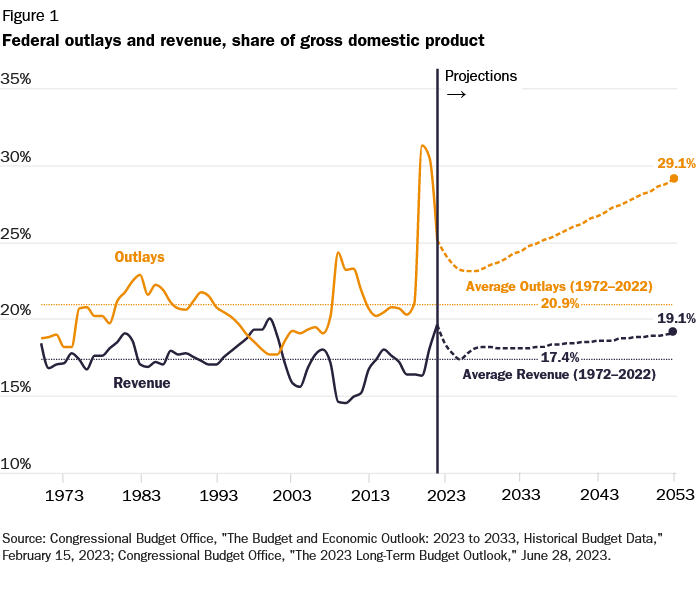

Since the 1960s, taxes have always brought in more money than the government spent. The average change in revenues has been about 17.4 percent of GDP, while the average change in spending has been about 20.9 percent. Between 1998 and 2001, when the economy was strong and tax revenue was high, Congress ran a surplus for a short time. This was because there was a temporary political consensus against deficits, which cut military spending, discretionary appropriations, and the growth of entitlements. Since then, spending has slowly gone up, with the Great Recession and COVID-19 being major turning points.

Figure 1 shows past and future income and spending from 1970 to 2053. In 2022, the share of federal revenue in GDP was at its highest level in 20 years. This year, the share of federal revenue in GDP is expected to be 18.4%, which is a whole percentage point higher than the average in the past. Over the next 30 years, earnings will stay above the average of the past 100 years, rising to 19.1% by 2053. After getting back to normal after the pandemic, spending is expected to rise past its current peak, going from more than 24% of GDP in 2023 to 29.1% of GDP in 2053.

There are some known problems with the CBO's forecasts. First, it is based on current law, which assumes things that aren't likely to happen, like Congress letting all the temporary tax cuts for 2017 expire and discretionary spending growing slower than the economy. Second, it doesn't take into account new spending that Congress will approve in the future, whether it's because of an emergency (like a war, recession, or disease) or because it's good for politics to pay off student loans or give more money to energy companies. Third, the forecasts are based on guesses about growth in the economy, inflation, interest rates, and the cost of health care. None of these problems change the most important thing to learn from the CBO projections, which is that the government budget can't be kept up even if taxes go up a lot and spending stays low.

Congress has done a much better job of limiting spending than of limiting how much money they expect to bring in. When benefits go up faster than inflation and more people become eligible for them, spending goes up. As temporary tax cuts run out and inflation slowly moves people into higher tax brackets, baseline tax income goes up. Inflation-caused real bracket creep will bring in more tax money over the next 30 years than the expiration of the 2017 tax cuts in 2053. It will bring in almost twice as much money as the end of the 2017 tax cuts.

Periodic tax cuts have kept the amount of money coming in as a share of the economy flat instead of going up, while spending growth has kept going up.

Taxes and Fiscal Sustainability

Some people have said, "Without the Bush and Trump tax cuts, debt as a share of the economy would be falling for good." But CBO budget estimates from before Bush's tax cuts in 2001 show a different picture. In 2000, when the U.S. had a budget surplus, the first line of the CBO's long-term budget outlook said, "The long-term budget outlook is dominated by projected growth in spending on the federal government's big health and retirement programs, Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security." Even in CBO's most optimistic scenario, in which the federal government saves the temporary surpluses, "the growing expenditures projected for health and retirement programs would quickly push the budget back into deficit," and the debt would again start to grow at an exponential rate.

Some recent years, like 2012, the CBO predicted that deficits and debt would go down. However, these years were just a fluke of the way the current law is scored, in which the CBO assumed both large automatic tax increases and large automatic spending cuts that Congress never meant to allow. The more realistic alternative baseline for 2012 expected that Congress would extend the tax cuts from 2001 and stop automatic payment cuts to Medicare providers, among other spending increases. This showed that deficits would grow to 17.2% of GDP by 2037 in this more realistic scenario.

Focus on Unsustainable Spending First

In the end, focusing on income takes attention away from fixing the fundamental financial problems the U.S. faces. The rate of growth of spending on health care and retirement is not something that can be fixed by raising taxes. Jeff Miron wrote in 2013: "If higher taxes have even a small effect on growth, they can't be used to bring the budget back into balance. This means that the only way to significantly reduce the budget imbalance is to cut spending, especially on Medicare, Medicaid, and subsidies for the Affordable Care Act.

CBO has been saying the same thing every year for the last few decades: spending on health care and retirement programs can't keep growing faster than the economy; finally, something has to give. Almost all of the growth in non-interest spending over the next 30 years will come from these big welfare programs, and their share of the economy is expected to grow by 36% over that time. This fast rise in spending on health care and retirement is neither caused by the tax code nor can it be fixed by it.

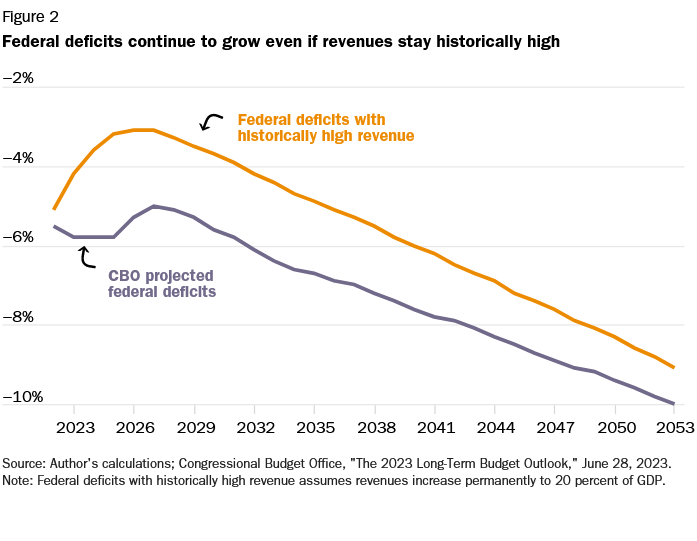

If Treasury brought in as much money as it did in 2000, when it had a record budget surplus of 2.3%, the U.S. would still have a budget deficit of about 5.1% of GDP in 2022 (instead of the real deficit of 5.5%). Figure 2 shows an example of what the government deficits would look like if tax revenue stayed at the high level of 20% of GDP from the early 2000s. The fact that CBO's current law projections only show slightly bigger deficits shows that even big tax hikes can't make up for spending growth that is basically unsustainable.

Debate the Level

After lawmakers figure out how to stop mandatory spending from growing at a rate that can't be kept up, they can talk about the right size and scope of government. People can have different ideas about how much the government should spend and, by extension, how much it should bring in.

I've written before that big government is expensive, and people who want a bigger government should be clear that when they blame deficits on tax cuts, they want middle-class Americans to pay a lot more in taxes. A European-style social welfare state can't be paid for by only taxing the rich more. This isn't a sustainable or financially possible way to pay for it. To pay for the government's current spending, let alone what some Democrats want to do, will take a tax increase that has never been seen before.

Widespread tax hikes are also not a sure way to bring down debts and debt. In the past, adding or raising taxes to fix fiscal problems has deepened and lengthened recessions, didn't lower the ratio of debt to GDP, and led to more spending than the taxes brought in.

As Congress gets ready for the fiscal cliff in 2025, when the tax cuts from 2017 expire and taxes go up for almost every American, lawmakers should make it clear that by keeping taxes low, they are also committing to keeping the level and growth of government spending in check. If people don't control their spending, any tax reduction will have to be short-lived.