Arkansas Tax Reform Then and Now: Next Steps on the Road Map to Competitiveness.

Major Changes to Arkansas’s Tax System since 2016

At the end of fiscal year 2023, Arkansas's state general income fund had more than $1 billion in extra money. Even though the COVID-19 pandemic and the 2020 recession have made the last three years tough financially, Arkansas ended the year with a large budget balance for the third year in a row. It was even bigger the year before, at $1.6 billion.

There was a lot of talk about what to do with these big budget reserves, but at their core, they show that Arkansas needs to change its policies: it needs to reform its taxes. These surpluses show that Arkansas's current tax system is bringing in a lot more money than the state's government has wanted to spend. The lawmakers only set aside $6 billion for general revenue in the last fiscal year, but the state tax system brought in over $7.1 billion in net revenue.

How should tax change go about it, though? Arkansas's General Assembly has already thought about this question. Since 2015, the government has changed and lowered taxes more than once. Arkansas has made many changes, and one of them is lowering the top percent income tax rates on both personal and business income taxes. This isn't the only change the state has made, though.

In 2016, right around the start of the most recent wave of tax cuts in Arkansas, the Tax Foundation and the Arkansas Center for Research in Economics worked together on a big research project that led to the release of Arkansas: The Road Map to Tax Reform. Many of the changes we suggested in that report were made during later congressional sessions.

Arkansas's top individual personal income tax rate was 6.9 percent in 2016, just a little less than its all-time high of 7 percent, which was set in the 1970s. Arkansas's nearby states had rates of only 5 or 6 percent, or even 0% in Texas and Tennessee. This rate was by far the highest of those states. Also, Arkansas's rate of 6.9 percent was the second highest in the South; only South Carolina had a higher rate, at 7 percent. In 2016, Arkansas's corporate income tax rate was also high, at 6.5 percent. However, it wasn't quite as out of the ordinary; Louisiana's rate was higher, at 8 percent, and a number of southern states, including Tennessee, were also at 6.5 percent.

The 2016 book told Arkansas what it could do to lower its personal and business rates to 5 or 6 percent, which would be more in line with other states in the area. The legislature has done everything we asked them to do to change the tax system. For example, they lowered the rate on personal income tax to 4.4% by 2024, which is more than what we asked them to do. The rate on corporate income tax will be close, at 4.8%. Over the next few legislatures, rates were slowly lowered, and in some cases, they weren't lowered until certain income goals were met (these are called "tax triggers"). But over time, the result is a big drop in income tax rates.

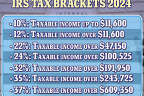

In addition to lowering the top income tax rate, our 2016 book advised a number of other changes that have since been made. For the individual income tax, we advised that the standard deduction be changed to account for inflation. This was in addition to changes made to most other parts of the tax code. This change was made during the special parliamentary session in 2021, which also passed one of the most important rate cuts. Arkansas's individual income tax had a complicated set of three groups of tax brackets in 2016. There were a total of 16 different tax rates based on a person's income. Many states have progressive income tax systems, but Arkansas had the most complicated one. Rates could go up even if someone's income was lower than certain levels ($21,000 and $75,000). To smooth out the "tax cliffs" that this system made, complicated refunds were added to the tax code. We said that this system should be streamlined into a single set of tax rates, even if those brackets were still progressive. Arkansas no longer has 16 tax levels, but there are now only two sets of eight. This goal has not yet been fully reached. As of 2023, Arkansas has a flat income tax system for people with taxable income over $25,000.

We also suggested a number of changes to the business income tax, in addition to the main rate cuts. For instance, we said that the state's "throwback" rule should be thrown out because it makes things too hard for some Arkansas businesses that do a lot of business outside of Arkansas. In 2023, this rule was taken away. As a first step toward treating the state the same as the rest of the country, we also suggested that the state's net operating loss carryforwards be increased from 5 years to 10 years. This is because most states and the federal government use 20 years or don't set a cap on years. This part of the tax code is very important for companies whose income change from year to year. It was also possible to start this first stage of change in 2021.

Like with the individual income tax, there are still important changes that have not been fully put in place yet. In 2016, we wrote a book that said Arkansas should stop giving specific tax breaks to businesses. These credits usually help firms that are liked by politicians without really helping the business as a whole. Some progress has been made, like getting rid of the InvestArk credit, which was the biggest program of its kind at the time. However, there is still a lot of work to be done in this area.

Along with changes to the income tax, the 2016 reform book also offered changes to the state's property and sales taxes. Arkansas also stands out in this way, but in two different ways: it has one of the highest sales tax rates in the country and one of the lowest effective property tax rates. One reason Arkansas has such high sales taxes is that towns and counties can choose to impose their own sales taxes. These taxes can be used to pay for a wide range of activities, and they can be put in place through special elections. Some work was made to stop local-option sales taxes from going up in the future. This was done by changing the law in 2021 and 2023 to limit the dates each year when these elections can be held.

The Future of Arkansas Tax Reform

Since 2016, a lot of changes have been made to Arkansas's tax system. What should we do now? As was already said, one thing is clear: Arkansas's tax system still brings in a lot more money than the state's lawmakers want to spend, even though tax rates have been lowered and other changes have been made. Surpluses of $1 billion a year are not likely to continue, but the government has set a budget of $6.2 billion for the 2024 fiscal year, and taxes are expected to bring in about $6.6 billion. That's not as much as last year's $7.1 billion, but it's still a lot more than what was actually spent. Changing the tax system so that it brings in more than $6.2 billion is an obvious step that could be taken right away and could pay for a number of important changes that need to be made. This is why tax cuts were passed in the special session, and if Arkansas's income keeps going up, it can make it easier to make more changes in the coming years.

It is always hard to say if there will be a national recession and how that will affect state spending. A real "rainy day fund," officially called the Catastrophic Reserve Fund, was set up in Arkansas in 2016. This is another important move that the state has made since 2016. Right now, that fund has about $1.5 billion in it, which is more than enough to make up for any drops in state income caused by a slowdown. In a special session, lawmakers also set up another reserve fund with a $700 million initial deposit. This is meant to be a safety net in case future tax income is lower than expected. Tax reform shouldn't focus too much on short-term changes in the business cycle. Instead, it should look at the steady state levels of tax revenue generated by the system and the present demands for state spending made by the legislature and executive branch, which were elected by the people.

It's also important to keep in mind that competing and nearby states have not sat still while Arkansas has lowered its income taxes over the past few years. Arkansas has tough competition in the area and across the country when it comes to taxes. In the last three years, 25 states have lowered their individual income tax rates. Five of the six states that neighbor Arkansas are among these states; Texas is the only one that has not done so because it does not have an individual income tax. The rates in all of Arkansas's nearby states are now or will be below 5% in the next few years. In 2026, Mississippi's rate will stay at 4%. To keep getting workers, families, and businesses to move to Arkansas, it needs to keep its taxes low and improve things like education, criminal justice, and infrastructure (like rural broadband). These are all things that the state's most recent governments have tried to do.

This publication continues the work we started in our last book, giving policymakers a plan for more change. It brings attention to work that hasn't been done yet, suggests next steps where some work has already been done, and helps politicians think about the pros and cons of some of the new tax ideas that have come up in Little Rock, such as the possibility of getting rid of the individual income tax.

Summary of Options

While individual income tax rate reductions have received the most attention from lawmakers, business tax reforms can provide substantial “bang for the buck” in facilitating greater economic growth and opportunity. In addition to corporate income tax rate reductions in line with any individual income tax rate cuts, lawmakers can and should:

Implement permanent full expensing, thereby reducing the tax code’s penalty on new capital investment Repeal the franchise tax, an archaic tax on a business’s net worth that bears no relation to its profitability or ability to pay Eliminate its nationally anomalous inventory tax, a highly nonneutral tax with substantial compliance costs which targets select businesses which must keep substantial inventory on hand Improve its treatment of net operating losses to better align with the taxation of long-term profitability, consistent with how most states treat such losses

For individual income tax rate reductions, we explore three options:

Triggered individual income tax rate reductions subject to revenue availability, with an estimated 7 years to get to 3 percent and 22 years to phase out the tax entirely Triggered individual and corporate income tax rate reductions in tandem, taking an estimated 8 years to reach 3 percent for the individual income tax, and 27 years for full repeal should lawmakers allow the reductions to continue Consolidation of the current dual tables into a single schedule based on the low-income filer rate

Each of these plans, and their revenue implications, are discussed in turn, along with revenue offsets should lawmakers wish to accelerate reductions (rather than waiting to phase them in slowly, paid for out of economic growth) or use other taxes to allow them to retain more of that growth. We also demonstrate a plausible rate reduction pathway should lawmakers choose to implement spending cuts. The trade-offs of each approach are considered, and a projected rank on the Tax Foundation’s State Business Tax Climate Index (a measure of the competitiveness of states’ tax structures) is provided.