Over the past 30 years, lawmakers have turned more and more to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) instead of traditional government agencies to get social and economic benefits through the tax code. As a result, the IRS now manages 21 refundable and non-refundable tax credits for individuals, such as the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and the Child Tax Credit (CTC), and about two dozen more tax breaks for corporations, such as the green energy tax credits made possible by the Inflation Reduction Act.

Because tax credits don't have the same built-in measurements and accountability as official spending programs, not much is known about how well they work. IRS data can tell us how many taxpayers claimed a tax credit and how much it lowered their tax liability, but it can't tell us if the credit changed taxpayer behavior or how they made decisions. But the IRS has to figure out how much "improper payments" of refundable tax credit schemes there are. Overpayments happen all the time in these programs because of mistakes, misunderstanding, or outright fraud on the part of taxpayers.

Tax credits lower a taxpayer's tax liability by the same amount that the credit is worth, and refundable tax credits are paid out when a taxpayer's tax liability goes down to zero. For example, if a taxpayer with one child is qualified for a $2,000 credit but only owes $1,000 in taxes, she would get half of the credit as a direct payment from the IRS and the other $1,000 would go toward her tax bill.

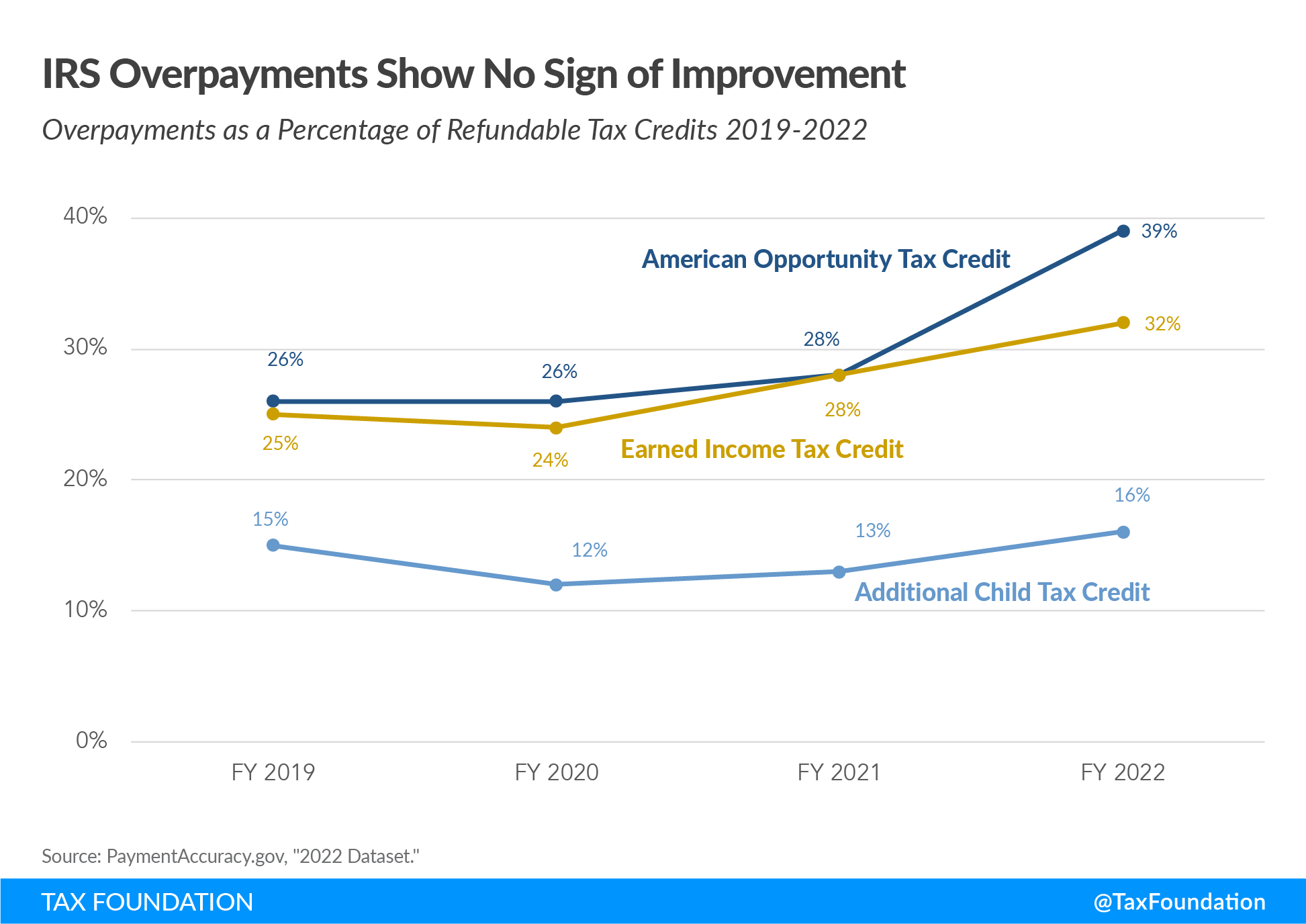

In 2022, 27% of tax credits that could be refunded were overpayments. In 2022, the IRS gave $98 billion in refundable tax credits to four programs: the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), the Additional Child Tax Credit (ACTC), the American Opportunity Tax Credit (AOTC), and the Net Premium Tax Credit (Net PTC). Recent reports from the Government Accountability Office (GAO) and the Inspector General for Tax Administration (TIGTA) of the IRS say that $26 billion in refundable tax credits were paid out too much.

But the IRS and the Treasury say that overpayments are not caused by bad management or problems with internal controls. Instead, the IRS says that overpayments are caused by things beyond its control, such as the "statutory design of the RTCs, reliance on taxpayers' self-certification of the accuracy of their returns, and the lack of third-party data for verification."

Maybe they're right. They may have also found the fatal flaw in trying to use the tax code to bring about social and economic gains.

The EITC, which is meant to help people who work but don't make much money, had the most overpayments. Nearly $1 of every $3 in EITC refund payments in 2022 were wrong, as shown in the table next to it. This was worth $18 billion out of the $57.5 billion in EITC refund payments.

The EITC has been giving out too much money for a long time. In fact, according to the information on PaymentAccuracy.gov, the EITC had an average mistake rate of 25% from 2004 to 2022. Taking inflation into account, the total amount of EITC overpayments over that 18-year time was $351 billion.

In 2022, the ACTC had made more money than it should have. 16 percent of the almost $33 billion in refundable CTCs that were given out in 2022 were overpayments. PaymentAccuracy.gov says that since 2019, ACTC overpayments have been nearly 14 percent on average and have added up to $22 billion.

At 36%, the AOTC had the highest rate of overpayments in 2022. The AOTC is supposed to lower the cost of college, but like the EITC, it has a long history of paying out the wrong amount. In fact, the TIGTA estimated that in 2012, "more than 3.6 million taxpayers (claiming more than 3.8 million students) received more than $5.6 billion in potentially wrong education credits ($2.5 billion in refundable credits and $3.1 billion in nonrefundable credits)."

The $2 billion in overpayments in 2022 are only due to mistakes in the part of the AOTC that is refunded. The IRS doesn't say how often mistakes happen with the part that can't be refunded.

Lastly, the net PTC is the part of the tax benefits for Obamacare, also known as the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, that is refundable. The IRS and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services work together to run the PTC. Even though the net subsidy is only $2.1 billion, there was an overpayment rate of 24 percent, which was extremely high.

Despite the IRS's best efforts, the number of overpayments has gone up, not down, in recent years. In fact, the image next to this one shows that since 2019, overpayments in the three biggest programs that give back tax credits have been going up. The AOTC overpayments have gone up the most, from 26% to 39%, while the EITC overpayments have gone up from 25% to 32% after a small drop in 2020. In 2019, 15% of ACTC payments were more than they should have been. In 2020 and 2021, the rate of overpayments went down, but in 2022, it went up to 16 percent.

Why can't the IRS stop people from being overpaid? The IRS says that overpayments happen because of things it can't change. In a lot of ways, the agency is right. Unlike most government benefit programs, the IRS can't choose who gets the benefit ahead of time. Traditional social benefit programs like Medicaid, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) have long application processes and case workers who question and pre-screen applicants to make sure they are eligible.

Tax credits and deductions are different. Tax gains are self-validating. In other words, it is up to the taxpayer (or their tax preparer or program) to figure out if they are eligible for the tax break. The only time the IRS can check if you're eligible for a credit is after you send in your tax return. Only then can the IRS use expensive tools, like computer software or an exam, to make sure a return is correct.

The IRS says it doesn't have access to the kind of third-party information it would need to verify the different family arrangements and other situations that can lead to errors, mistakes, or fraud in both the EITC and CTC programs. In the 2022 Annual Financial Report from the Treasury, it says that if the IRS had access to this kind of information, it would be invasive and only provide a small gain compared to the cost.

The Office of Management and Budget wants the IRS to get the number of mistakes that lead to overpayments to less than 10 percent. The IRS says it can't do that. Treasury says that the IRS would need an extra $2.5 billion to look over 4.2 million EITC forms before giving out refunds.

Treasury agrees that such a plan would not work. In fact, they know that the high audit rates for the EITC, in particular, are a problem for public relations. "The IRS spends a lot of time and money on auditing tax returns that claim one or more RTCs. This makes things hard. Because most RTC claimants have low incomes, they are audited about three times as often as other taxes. They admit that this "can make people feel bad about how the IRS treats taxpayers."

Treasury says that 15 percent of the tax gap caused by people not reporting enough income tax is due to tax credits. The EITC makes up 10% of the tax gap by itself. But Treasury seems to imply that we may have to live with overpayments by saying that if the IRS were forced to put more audit resources into refundable tax credit returns, it would cause "a substantial loss in enforcement revenue, estimated at $6.4 billion," because the IRS would have to take resources away from programs with higher returns and tax gap elements to audit RTC returns.

Other design problems also make it hard for customers to understand and give the IRS trouble with running its business. For example, each of these refundable tax credits has a different meaning of "income," different rules for different types of families, different residency requirements, and other things that make it easy for mistakes and fraud to happen.

Treasury also says that paid preparers are partly to blame for the mistakes or theft. More than half of taxpayers who get the EITC pay someone else to help them fill out their tax forms. The IRS says that unenrolled return preparers are often less prepared to handle complicated returns like the EITC.

The IRS was designed to fail. Because of how tax refunds are made, the IRS is in the same position as a police officer who gets to the scene of a crime after it has already happened. Since the IRS can't check out taxpayers before they use the programs, the only way to make sure a claim is true is through audits or complicated computer formulas after the fact.

Lawmakers have made things worse by making programs with confusing eligibility rules that confuse customers and raise the IRS's administrative costs. Lastly, tax programs don't have built-in measurements or goals that can be measured, so the IRS can't tell how well they work.

These things show that politicians should try to avoid giving social and economic benefits through the tax code as much as possible and instead work to simplify or get rid of the tax expenditures that are already in the code.