Rep. Jason Smith (R-MO) introduced a bill this month that would tell the Treasury to make a list of countries that tax U.S. taxpayers (including businesses) in unfair or extraterritorial ways, and then raise taxes on companies and people from those countries.

As the UTPR is a new concept, it is worth explaining what it is and why Rep. Smith cares about it. In a sentence, the Undertaxed Profits Rule (UTPR) is a looming extraterritorial enforcement mechanism for a tax base the U.S. has not adopted.

The Tax Base

First, let's talk about the question of the tax base. The UTPR is based on corporate income, and it is part of the OECD's plan to figure out some tricky international tax problems. It is paired with a set of other rules called "Pillar Two," which try to set a minimum effective corporate income tax rate of 15 percent around the world.People think that if tax officials don't work together, corporations may try to get rates even lower than 15%, especially for intangible parts of their business like intellectual property, which can easily be "moved" around the world to the place where taxes are the lowest.

But Pillar Two can't just have rules about rates. A tax rate without a tax base isn't even a tax rate. For example, a 15 percent tax rate where people can deduct half of their income from their taxable income is more like a 7.5 percent rate. So, Pillar Two tries to avoid this problem by describing not just a tax rate but also a tax base.

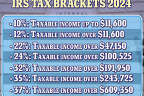

Most of the time, U.S. tax rates are in line with Pillar Two. The top domestic tax rate in the U.S. is 21%, and even for highly mobile foreign or intangible income, the U.S. has rates that are close to the minimum of 15% through provisions like Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income (GILTI) or Foreign-Derived Intangible Income (FDII).

But the U.S. calculates corporate income differently than the rules in Pillar Two because "income" is much harder to describe in real life than it is to think about in theory. Also, Congress has often used tax policy for things other than keeping an exact percentage of income, whether that percentage is measured by the IRS, accounting rules, or something else. In 2022, Congress, for example, added a number of tax credits for green energy.

Because of these two problems, it's possible that U.S. companies with tax rates above 15% by U.S. standards or companies that take advantage of features of the U.S. tax code could end up below the 15% target for Pillar Two because of differences in measurement standards or because the rules for Pillar Two don't allow for U.S. credits.

Non-Adoption by the U.S.

Pillar Two does give a country a way to get its companies to follow the rules. The 15 percent rate can be made sure of by using both an Income Inclusion Rule (IIR), which brings foreign companies up to the minimum, and a Qualified Domestic Minimum Top-up Tax (QDMTT), which brings domestic income taxes up to the OECD minimum.But the United States has not taken on these rules. Under the Biden administration, the U.S. Treasury Department has been in favor of the bigger project, but Congress has not taken these steps for a number of reasons. First, the Pillar Two framework isn't that old, so the U.S. hasn't had much time to get in line with the rules, and there isn't any instant money to be made by getting in line with the Pillar Two base. In general, Republicans have been doubtful about how good the project is. In their most recent company tax reform, Democrats put in place a different domestic minimum tax that has the same 15 percent rate as the OECD but not the same Pillar Two base. And members of Congress from both parties might not like the idea of giving an international group control over the tax base in the United States.

Extraterritorial Enforcement

This gets us to the UTPR, which is one of the most controversial parts of the OECD project. It gives countries a financial reason to adopt tax systems like those in Pillar Two. Think about a multinational company (MNE) that meets the requirements of Pillar Two and has at least some low-tax income, either in its home country or in its foreign businesses. Under the UTPR, if its home country doesn't have a QDMTT or IIR, other countries can step in and collect the top-up tax instead, almost like a home country that meets Pillar Two. In particular, the only other countries that could charge the UTPR would be those where the global company has a presence. If more than one country is allowed to charge the UTPR, these other countries would get a share of the money based on how much of the company's assets and workers are in their country. Even though the UTPR is technically a tax on the business and not the parent company, its amount is based on the tax profile and income of the parent company. This means that it has the same effect on the whole group as a QDMTT and IIR.There are a few technical differences between IIRs and UTPRs in unusual situations like partial ownership, but they both serve the same goal. The UTPR is often called a backstop.

The IIR, on the other hand, is in line with existing international law standards and controlled foreign company (CFC) rules. The UTPR, on the other hand, has never been seen before in international law, as five legal experts recently wrote in Tax Notes. With a few exceptions, international law has usually tried to stop countries from trying to tax each other's domestic tax bases. This is to avoid double taxation. The UTPR agrees with this method.

In the past, governments could only tax the worldwide income of multinational corporations (MNEs) whose parent company was based in their country. In other words, Germany might be able to get money from the small foreign companies of a German company. But the countries where the small subsidiaries were based couldn't ask for money from the main company. The UTPR turns that around, in theory letting countries where an MNE has a foothold claim some sort of control over the whole thing.

Giving the same income to more than one country has always been a tricky situation. Even if there were clear rules about apportionment in theory, countries would still have strong reasons to argue over accounting details. For example, they might see their own business subsidies as spending policies that have nothing to do with Pillar Two, but see the business subsidies of other countries as reductions in the effective tax rate that should lead to a UTPR.

Legal experts in Tax Notes say that new policies that go against traditional international rules can still be accepted over time under "customary law," but UTPRs are still not settled. The Republic of Korea might have a UTPR by 2024, and European Union countries might have them by 2025, but as of right now, they are not in effect anywhere on Earth, and the U.S. Congress is against them. More generally, Pillar Two rules will conflict with tax policies around the world, both those that are already in place and those that countries might make in the future, which could lead to resistance. The cost of Pillar Two to fiscal sovereignty is high, and Rep. Smith seems likely to vote against it.