The Fed is insolvent, and that means that it will bail itself out by printing money. For ordinary people, that means inflation and a rising cost of living.

In 2011, the Federal Reserve invented new accounting methods for itself so that it could never legally go bankrupt. As explained by Robert Murphy, the Federal Reserve redefined its losses so as to ensure its balance sheet never shows insolvency. As Bank of America’s Priya Misra put it at the time:

That happened twelve years ago, and at the time, it was all academic. But in 2023, the Fed is really broke, even though this doesn't show up in its fake account after 2011. Still, the Fed's assets are losing value and it is paying out more interest than it is making in interest income.As a result, any future losses the Fed may incur will now show up as a negative liability (negative interest due to Treasury) as opposed to a reduction in Fed capital, thereby making a negative capital situation technically impossible.

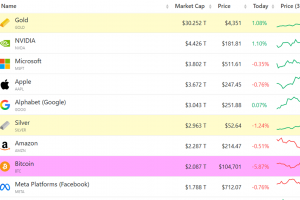

This became clear when the Fed released a new report last week showing that in 2022, the interest it paid on bank reserves would skyrocket. The press release states:

Total interest expense of $102.4 billion increased $96.6 billion from 2021 total interest expense of $5.7 billion; of the increase in interest expense, $55.1 billion pertained to interest expense on Reserve Balances held by depository institutions and $41.5 billion related to interest on securities sold under agreements to repurchase.

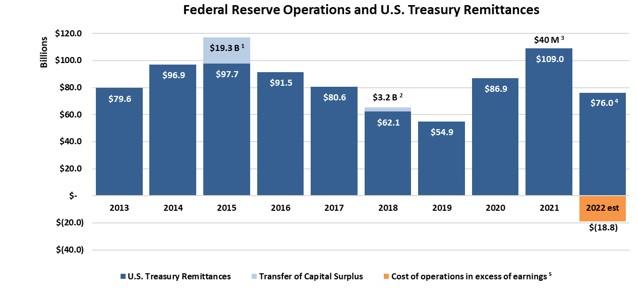

As this graphic from the Fed shows, the cost of operations also exceeded earnings in 2022 because remittances have fallen from 2021:

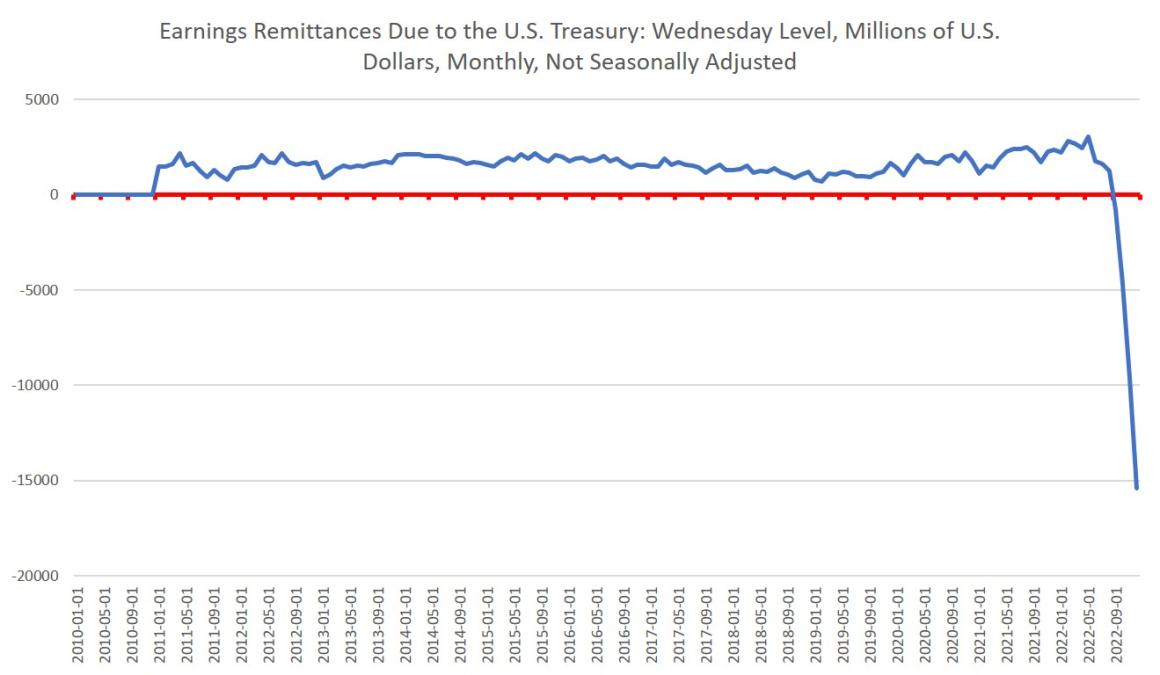

The Fed still had a positive net income for the year as a whole because of the money that came in during the first half of the year. But since September, Reuters says, the Fed has been keeping track of its loss with something called a "deferred asset." At the end of the year, the deferred asset was worth $18.8 billion.Fedspeak for "losing money" is "deferred asset." The Fed is supposed to send money to the US Treasury out of its surplus, but when it doesn't have any extra money, it "defers" its payments. We can see how these money transfers went into the red starting in September:

The trend of falling remittances is unlikely to reverse in 2023, unless the Fed takes a very dovish turn and forces interest rates down again. What is more likely is that the Fed will hold rates flat or only slightly reduce them. In either case, the Fed will have to keep paying out more in interest than it makes in income.

Why Is the Fed Insolvent Now?

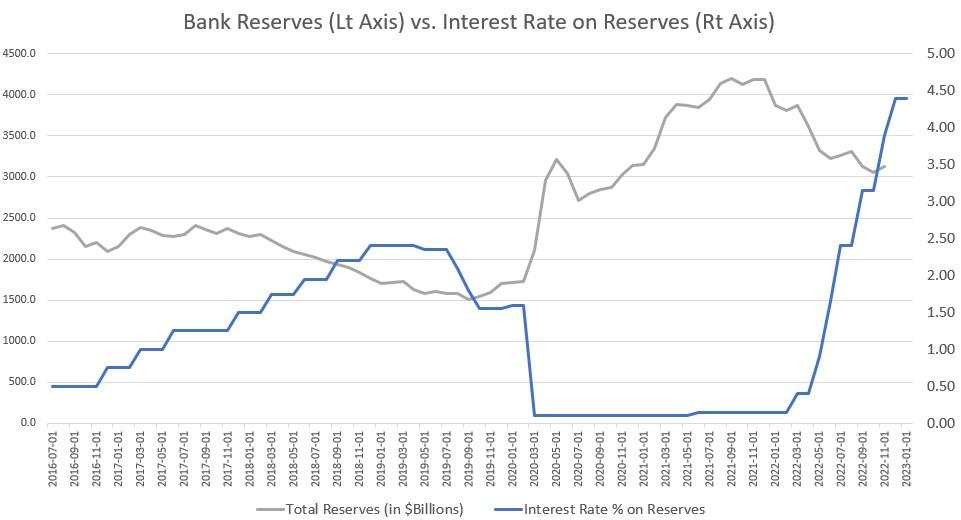

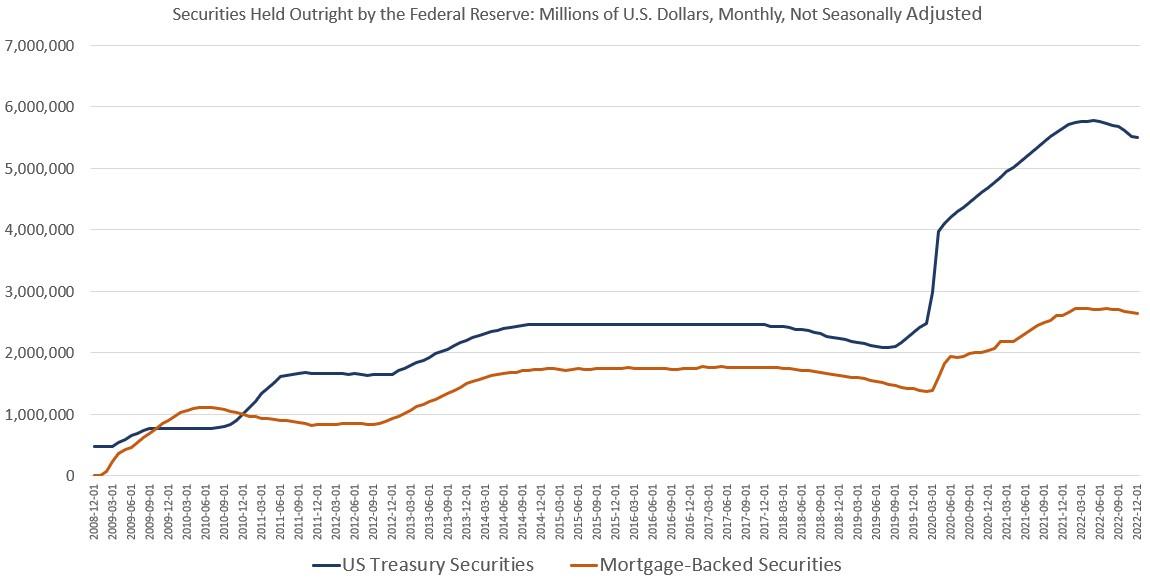

Since 2008, the Fed has bought up trillions of dollars in Treasury debt and mortgage-backed securities. This is a big reason why the Fed has become bankrupt in recent months and almost certainly will be bankrupt by 2023. (MBSs). The Fed did this to keep the prices of homes and government bonds from falling (i.e., to subsidize Wall Street, banks, and the real estate industry.)But it bought these fixed-rate assets when interest rates were very low, and most of these assets have a maturity of more than a year. This means that even though interest rates have gone up in the past year, the Fed hasn't made much more money from these assets. Still, the Fed pays interest to banks on their reserves and reverse repos. The interest rate on that loan is not set, and it changes quickly. So, even though the Fed's total reserves have gone down by 25% in the past few months, interest payments won't go down to 2021 levels because interest rates have gone up by 4,300%, from 0.1% to 4.4%. How did it turn out? The Fed is now giving out more interest to banks than it makes from the MBSs and government bonds it holds in its portfolio. So, as we saw in the Fed's Friday report, interest payments have gone up, but income has not. This means that the Fed has to put off payments to the Treasury that it had promised to make.

The Fed's portfolio is also losing value, which makes things even worse and pushes it further into the red.

(If you remember that bond prices move in the opposite direction of interest rates, you'll see why this is a problem. So, when the yields on newly issued bonds go up, the prices of existing bonds go down.

In the past year, as interest rates have gone up, the value of the Fed's MBSs and Treasury debt has gone down. So now the Fed has less money as well. Unlike Enron, however, the Fed's bankruptcy is just a matter of "deferred assets" in the eyes of the law, so it's not a problem for the Fed. Still, we've seen this kind of problem before, so we know that the Fed's losses are likely to get worse and that it will need help. Alex Pollock said in a 2022 lecture at the Mises Institute that the Fed is in a similar situation to the savings and loans industry in the early 1990s. The Fed "invested" in a lot of long-term debt with low fixed interest rates, just like the S and Ls. The rates of interest went up, though. The fixed-rate interest income stayed mostly the same, but the amount of interest that had to be paid went up by a lot. Right now, the Fed is there.

For a normal bank, this is a situation that leads to going bankrupt. But the Fed will print money to save itself. In the end, that means prices will go up, either for assets like stocks and real estate or for consumer goods like eggs and auto parts. The cost of living will go up for most people, while their real wages will go down. This means that most people will get poorer. In spite of everything, though, both the Fed and the regime will be better off. In recent days, the Fed has been careful to say that its "de facto" bankruptcy doesn't stop it from doing its usual inflationary monetary policy. Don't worry—the regime will continue to benefit from the Fed's usual tricks because the Fed can create its own income whenever it wants to through monetary inflation. The government will be able to run bigger deficits and spend more on "free" benefits for voters and corporate handouts for powerful people. All of this is a great trick for the parasitical class. For the people who work? Not really.