Pension funds after the gilts crisis: the big asset allocation rethink

When UK pension funds started to buckle under the turbulence caused by the Truss government’s “mini” Budget in September, senior executives at J Sainsbury were taking no chances.

The supermarket group’s pension fund, which has more than 70,000 members, had weathered the initial market volatility. But the company, fearful of more ructions once the Bank of England stabilisation measures were withdrawn, hurriedly set up a loan facility for £500mn.

“We decided to put a short-term loan in place should [the pension fund] require it,” said Sainsbury’s chief financial officer Kevin O’Byrne. “If there was a spike [in gilt yields] . . . we didn’t want them to have to do anything irrational like selling assets at the wrong time.”

An important part of that approach has been the growing use of LDI by pension funds. But when gilt prices plummeted after the “mini” Budget announcement of unfunded tax cuts, counterparties made urgent demands for more cash as collateral to keep the hedging arrangements in place and the strategy came unstuck.

Pension funds became forced sellers of assets to meet these collateral calls. They dumped gilts, causing prices to fall further, and also slashed their holdings in the most liquid securities, such as corporate bonds and equities.

“There’s been more activity in pension schemes in the past month than there has been in the past five years,” says Alex Millar, head of UK distribution at $1.3tn asset manager Invesco.

Sarah Breeden, a member of the Bank of England’s Financial Policy Committee, said on Monday that LDI funds sold £30bn of gilts and raised over £40bn in funds during the period of market turmoil. “The root cause is simple,” she said. “Poorly managed leverage.”

But the irony for DB schemes is that while the sharp swings in the gilt markets wreaked havoc on liquidity, their overall funding positions have actually improved dramatically. This is because the steep rise in interest rates has shrunk liabilities faster than asset values have declined, as higher yields reduce outstanding obligations to retirees.

It means that schemes are now much closer to what is known as “buyout”, when a fund pays an insurance company to take over the pension payout promises and the corporate sponsor offloads the pension fund risk. This has implications for their asset allocation.

“As pension funds get closer to buyout they will want to have less market risk, and higher capital buffers will be required for their LDI strategies,” says Peter Harrison, chief executive at FTSE 100 asset manager Schroders. Both of these reasons “will force DB pension funds to be sellers of growth assets”.

The momentum is likely to accelerate as schemes offload illiquid holdings, such as private equity and infrastructure, to better position themselves for buyout. A trustee at the pension scheme of Airbus, the world’s largest aircraft maker, says it plans to reduce risk and add to its LDI hedge as it moves closer to buyout. It will gradually reduce its property and infrastructure portfolios.

The UK DB market is now on a £155bn surplus compared to a £600bn deficit a year ago, while liabilities have shrunk to £1.2tn from £2.4tn, according to professional services firm PwC. JPMorgan has forecast that £600bn of DB pensions could be bought out over the next decade, more than double the rate of the past 10 years.

Harrison says that pension funds will become “more circumspect” about investments in other assets. “The future fundraising for parts of private equity is going to be much tougher,” he says.

The end of the Great Moderation

Even before the pensions drama in the UK, institutional investors were already revisiting many of their core assumptions.

“This is an exceptional year for asset allocation,” says Stephen Cohen, head of Europe, Middle East and Africa at BlackRock, the asset management group. “It’s the end of the Great Moderation,” he adds, referring to the long period of steady growth, falling interest rates and lots of liquidity in the markets. “Conversations with investors are around high inflation, more volatility and rising interest rates.”

In addition to these market forces, there is the war in Ukraine, global energy and food crises, supply chain disruption, and geopolitical tensions between the US and China.

Historically stocks and bonds were seldom correlated for long periods, but this year they have fallen in tandem, leaving investors questioning how to balance risks in their portfolios.

“The difficulty you have as a multi-asset investor this year is that it’s been virtually impossible to find diversification,” says Jon Cunliffe, managing director of investments at pensions provider B&CE.

“There is nowhere to hide for investors,” says Fiona Frick, chief executive of Swiss asset manager Unigestion. “Our clients are in freeze mode at the moment.”

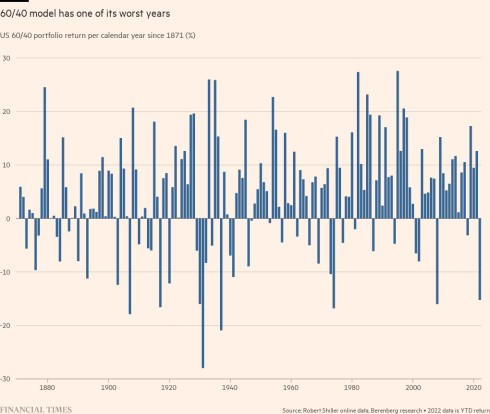

The positive correlation between equities and bonds has undermined the 60/40 balanced approach, where investors allocate 60 per cent to equities, for capital appreciation, and 40 per cent to bonds, to potentially offer income and risk mitigation.

It’s been “a nightmare for allocation,” says Mortier at Amundi. “The 60/40 model has been broken for some time and totally broken for a year.”

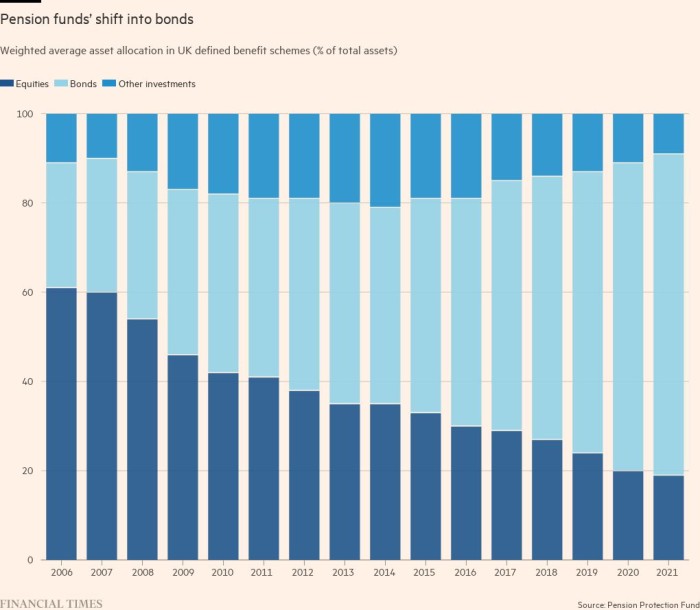

Investment managers do not believe, however, that the result will be a return to most assets being invested in equities — as was the case two decades ago.

Amundi says it is seeing more requests from clients for diversification — both across sectors and beyond developed markets to Latin America, China and India. “People are thinking differently,” he says. Instead of thinking in terms of equities and fixed income, investors are thinking about “risk factors” that cut across asset classes.

Mortier believes that 60/40 will “make a comeback” next year as central banks pivot, equities reprice and inflation starts to come down. “Bonds and equities will have a negative correlation again.”

Sonja Laud, chief investment officer at LGIM, says that a “regime shift” to higher yields on government bonds means there is less of a need for funds to move into illiquid but higher-returning credit assets. “With yields where they are now, a lot of government and corporate bonds will be more attractive.”

Cohen at BlackRock says: “We’re starting to see a lot of clients talking about fixed income becoming interesting again.”

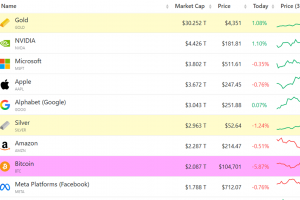

Pension funds pushed into riskier credit as a result of the hunt for yield but now that some sovereign bonds are yielding 4 or 5 per cent they do not need to go that far down the risk spectrum. “What that does to asset allocation could be pretty profound,” says John Graham, chief executive of CPP Investments.

While the next few months look difficult, pension funds who have a longer-term time horizon say that they are beginning to see buying opportunities in both bonds and shares. Cunliffe says: “Bond yields are at the highest they’ve been since the global financial crisis and equity valuations are below the 20-year average, which is not a bad starting point . . . to get a decent return in the next three to five years.”

Driving the economy

The gilt market turmoil was sparked by the government and it is a government plan that could be one of the casualties of the ensuing fallout.

With DB pensions being phased out by many companies, the bulk of pension savings are now invested in defined contribution (DC) schemes, where members draw a pension from their individual pot and take their own investment risk.

The UK government has identified the potential of the DC industry, with more than a trillion pounds of assets, to help drive economic growth and the transition to a green economy. A survey commissioned by the Department for Work and Pensions found that two-thirds of DC schemes do not invest in illiquid assets, while the remaining third invest less than 7 per cent.

In recent years Westminster has made successive attempts to encourage the schemes to redirect more of their cash to projects that will help drive the UK’s economy, such as infrastructure projects, tech start-ups and wind farms.

Tuntum Housing Association, set up more than 30 years ago by a number of activists from Nottingham’s black community to supply quality affordable housing, is an example of the sort of organisation the government plans could support. Tuntum’s backers include institutional investors such as Phoenix Group, which invests about £10bn in illiquid assets including infrastructure and social housing, part of a push to help address the challenge of housing shortages across the UK.

These sorts of assets have “a lot of structural appeal” for UK pension funds because they expose them to long-dated cash flows, provide a hedge against inflation and allow them to plough capital back into the UK, says Vivek Paul, head of portfolio research and UK chief investment strategist at BlackRock Investment Institute.

The government push extends to reforming so-called Solvency II rules, adopted while Britain was in the EU, to allow insurance companies to invest billions of pounds more in infrastructure. It is also approving a new “long-term asset fund”, or LTAF structure, that is designed to give businesses and projects great access to capital from investors such as pension funds that have a long-term investment horizon.

State-backed pension fund Nest, one of the UK’s largest workplace pension schemes, is among the DC plans ploughing money into private assets. “We think there is room for us to take on more exposure to illiquid assets, particularly for younger members,” says Liz Fernando, deputy chief investment officer at Nest. “They’re particularly well-suited to taking on liquidity risk and being rewarded for it.”

However, the downside of such investments is they could result in millions of low- and middle-income savers paying the higher fees that such projects usually charge, with no guarantee of improved returns.

“Moving into illiquids does come at a cost, with no guarantee of improved returns, so you do have to take a leap of faith,” says Steven Cameron, pensions director of Aegon, a pension provider with 3mn customers. He worries that the recent liquidity crisis in the DB world may give DC schemes pause for thought: “Trustees of DC schemes may be more wary of going into illiquid assets . . . this could impact the LTAF because DC trustees might be more cautious now on illiquids.”

While DC schemes in theory have a long-term time horizon, they offer daily pricing to allow investors to transfer in and out of funds at will using up-to-date valuations for those assets. This could be hard to square with the government’s push to encourage more investment in inherently hard-to-sell assets, which are valued far less frequently.

Stephen Scholefield, senior partner at law firm Pinsent Masons, adds: “Because of [the recent] experience I don’t think DC trustees will be rushing to go into any form of illiquid investments, even though this is what the government is encouraging.”

Others worry that political turbulence in the UK has become an obstacle. LGIM’s Laud says: “If you want to attract private capital you have to provide certainty that the regulatory framework is not going to be subject to random change and reassure investors that economic considerations of these projects won’t be derailed by the political outlook.”

Additional reporting by Adrienne Klasa in London

This story originally appeared on: Financial Times - Author:Harriet Agnew