The clear election victory for Republicans means they will retake the White House, Senate, and (by a slim margin) the House next year, putting them in the driver’s seat to determine the direction of tax reform. Republicans are likely to use a process called budget reconciliation, which allows for budget legislation to be passed out of the House and Senate via a simple majority.

The clear election victory for Republicans means they will retake the White House, Senate, and (by a slim margin) the House next year, putting them in the driver’s seat to determine the direction of tax reform. Republicans are likely to use a process called budget reconciliation, which allows for budget legislation to be passed out of the House and Senate via a simple majority.

Fiscal pressures are likely to weigh heavily on lawmakers as they craft a tax reform package. That increased pressure could result in well-designed tax reform that prioritizes economic growth, simplicity, and stability, or it could encourage budget gimmicks and economically harmful offsets. Lawmakers should avoid the latter.

What Is Reconciliation?

In 2017, Republicans used reconciliation to pass the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), and Democrats used it for the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) in 2021 and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) in 2022. Reconciliation is a fast-track option to enact tax, spending, and debt limit changes outlined in a budget resolution.

Lawmakers can specify targets or limits on reductions or increases in the deficit within the budget window. The “Byrd rule” limits what can be included in a reconciliation bill, disallowing policy changes that don’t affect spending or revenue, and disallowing changes that increase the deficit outside of the budget window. Reconciliation also specifically prohibits changes to Social Security.

What Tax Cuts Are on the Table?

On the campaign trail, Trump promised $7.8 trillion of tax cuts and only $4.7 trillion of offsets, leaving a proposed deficit increase of $3 trillion. Reconciliation rules and greater concern about deficits and debt will limit how much of President-elect Trump’s tax agenda can be passed in 2025.

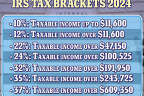

Trump and congressional Republicans aim to extend the TCJA’s temporary provisions, which expire after 2025. We estimate permanence for the individual, business, and estate provisions would add about $4.25 trillion to the deficit from 2025 to 2034 on a conventional basis. On a dynamic basis, including economic growth effects, the cost drops to $3.59 trillion—meaning economic gains offset 16 percent of the cost.

The Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) estimated the budgetary impact of a slightly different set of TCJA provisions, finding a direct revenue loss of $4 trillion plus $605 billion in higher interest costs. JCT does not model restoring full expensing for research and development (R&D) or the EBITDA-based interest limitation as part of its $4 trillion extension cost, whereas we do. JCT does include international changes and Opportunity Zones, whereas we do not.

On top of TCJA permanence, Trump proposed lifting the cap on the state and local tax (SALT) deduction, exempting tips and overtime pay from income tax, exempting Americans abroad from income tax, allowing auto loan interest to be deductible, and lowering the corporate tax rate to 15 percent for domestic production. We estimate these tax cuts would reduce revenue by $2.4 trillion. Trump also proposed a new tax credit for family caregivers without providing specifics, but the idea has bipartisan support in the House and Senate.

Trump’s proposal to exempt Social Security benefits from income tax would likely not be permitted under reconciliation rules because it would affect Social Security funding.

In total, if Trump’s tax cut proposals were pursued fully in reconciliation, the conventional revenue loss would be about $6.7 trillion from 2025 to 2034 before counting his proposed offsets. The dynamic score would be about $500 billion lower. Notably, reconciliation procedures disallow policies that increase deficits outside the budget window.

Table 1. Trump’s Campaign Tax Proposals

| Policy | 10-Year Revenue, Conventional, Billions |

|---|---|

| TCJA Individual Permanence | -$3,392.1 |

| TCJA Estate Tax Permanence | -$205.6 |

| TCJA Business Tax Permanence | -$643 |

| Restore Full Deduction for SALT | -$1,040.5 |

| Lower Corporate Rate to 15% for Domestic Production Activities | -$361.4 |

| Exempt Social Security Benefits from Income Tax* | -$1,189.1 |

| Exempt Overtime Pay from Income Tax | -$747.6 |

| Exempt Tips from Income Tax | -$118 |

| Create an Itemized Deduction for Auto Loan Interest | -$61 |

| Exempt Americans Abroad from Income Tax | -$100 |

| Repeal IRA Green Energy Tax Credits | $921.1 |

| Impose a Universal 20% Tariff on All Imports Plus Additional 50% Tariff on Imports from China | $3,823.9 |

| Total of Items That Might Be Considered Under Reconciliation | -$1,924.2 |

*Not permitted under reconciliation rules.

Source: Tax Foundation General Equilibrium Model.

Republicans in Congress have shown support for some but not all of Trump’s tax cut proposals, and they have introduced ideas of their own, such as retroactive extension of the business provisions, which could add more than $200 billion in additional revenue losses.

Senator Barrasso (R-WY) has introduced a bill to repeal the IRA’s corporate alternative minimum tax (CAMT), and Congressman Arrington (R-TX) has introduced similar legislation in the House. Republicans could also repeal the IRA’s other revenue raisers, including the share buyback tax, drug pricing controls, and additional funding for the IRS, potentially adding another $800 billion or more in revenue losses.

How Could Policymakers Pay for It Under Reconciliation?

Trump’s major proposed offsets are steep increases in tariffs and repeal of the IRA green energy tax credits. We estimate a universal tariff of 20 percent combined with a 60 percent tariff on imports from China would raise about $3.8 trillion, while full repeal of the green energy credits would raise another $921 billion, reducing the net budgetary cost of Trump’s tax and tariff proposals to $1.9 trillion from 2025 to 2034.

However, the tariff revenues would only count toward reconciliation if they were legislated, and it seems unlikely that congressional Republicans would support such a large increase in tariffs (leading to the highest tariffs since the Great Depression). More likely, congressional Republicans would set their deficit target for reconciliation higher while unofficially relying on tariff revenues they anticipate from Trump’s executive action.

In that case, even with full repeal of the IRA tax credits, and including dynamic effects, a reconciliation bill that includes all potential tax cuts described above could add approximately $6-7 trillion to deficits over a decade. To conform to reconciliation procedures, this combination of policies would either need to be temporary or paired with larger offsets moving forward to avoid increasing the deficit outside the budget window.

It is unlikely that policymakers would vote for a $6 trillion or higher deficit target for reconciliation. In 2017, Republicans agreed to a $1.5 trillion deficit increase, balancing concerns about the debt with a desire to boost economic growth. Since then, the federal debt has grown more concerning—publicly held debt as a share of GDP was about ¾ the size of the economy in 2017, but now it’s about equal to the size of the economy and headed higher.

Is there a Path Forward for Tax Reform?

One obvious option is to extend TCJA and other tax cuts on a temporary basis, as was done in 2017. Temporary extension nullifies the long-term boost to economic growth and amounts to a budget gimmick. Instead, policymakers should prioritize growth and fiscal responsibility, which requires permanent, well-designed policy changes. Changes to further simplify the tax code and make it more neutral across industries and taxpayers could ease the burden of compliance and make tax rules more administrable.

By that standard, full expensing for capital investment, including for equipment and R&D, dominates the other tax cut ideas floated on the campaign trail. Expensing or equivalent treatment should be extended to include structures, which would boost the supply of housing, offices, factories, and other buildings. To simplify saving and improve financial security for individuals, lawmakers could adopt universal savings accounts (USAs) and reform other saving incentives.

The TCJA’s lower individual income tax rates, alternative minimum tax relief, and higher estate tax exemption, along with other simplifying reforms, should also be priorities. To offset the revenue losses, continuing the TCJA’s base broadening is paramount, though loosening the SALT cap may be necessary to maintain support for its continuation (we estimate doubling the cap to $20,000 for joint filers would add about $173 billion to the 10-year cost of TCJA extension).

Reassessing the IRA, including requesting a new score of its more complicated aspects, such as the CAMT and green energy tax credits, should also be on the table for reconciliation.

Another option is to consider spending reforms. Trump has indicated support for reductions in spending outside of defense, Social Security, and Medicare. Outside of these programs and interest on the debt, the federal government is projected to spend about $30 trillion over the next decade. While many Republicans in the House support deep spending cuts, that is unlikely to receive broad support, meaning spending cuts are unlikely to be a major offset in reconciliation.

If Republicans are serious about legislating new taxes to offset TCJA extensions, they should consider a well-designed consumption tax—not tariffs. We estimate that a 1.5 percent broad-based value-added tax would raise $2.3 trillion over the 10-year budget window—more than a 10 percent universal baseline tariff, without running afoul of international obligations or inviting retaliation from trading partners.

There are several other revenue-raising options that would do relatively little damage to the economy, including repealing tax preferences for certain industries and types of compensation.

Revisiting the early inspiration of the TCJA and considering replacing the corporate and individual income tax with a border-adjusted tax on business profits and a progressive tax on salaries and wages—in effect a flat tax that applies to imports and exempts exports—could greatly improve incentives to work and invest in the American economy while simplifying the tax code and raising sufficient revenue.

Another option to overhaul the income tax system would be to emulate the Estonian approach, consisting of a distributed profits tax in lieu of our current complicated business tax system and a simple individual flat tax. We have shown that adopting this style of reform would boost economic output substantially, raising GDP by 2.5 percent over the long run, boosting wages by 1.4 percent, and adding 1.3 million jobs while funding the federal government at or above current levels. By dramatically simplifying the tax system it would reduce compliance costs by at least $100 billion annually.

Now is the time to think boldly and clearly about what is at stake. Economic growth is a function of policy and tax policy is a key lever. Republicans can simultaneously solve perhaps the two largest policy challenges America faces by reinvigorating economic growth and putting the federal government’s fiscal house back in order. It is an opportunity that should not be wasted.