The phrase 'free markets have many problems that government must step in to solve' has been repeated innumerable times in my more than 25 years of educating undergraduate students.

Given that college students have been inundated with stories of government solutions to societal problems from the media, teachers, and parents starting in elementary school, this is not surprising. Once kids learn about "market failure" in their first economics lesson, it doesn't take much to persuade them that free markets are at best unworkable and at worst a flimsy justification for capitalist exploitation. Most professors won't stray too far from the widely used textbooks, and the most popular economics textbooks at the college level don't do much to dispel these misconceptions.

At least one chapter in most textbooks on principles of microeconomics and intermediate microeconomics is devoted to the topic of market failure, which is frequently characterized by "market power" (think monopoly), insufficient "public goods" (items that the private sector allegedly won't produce enough of because it can't get the users to pay), and "externalities" (the unintended consequences of human activity on bystanders, like pollution). Although textbooks typically make some mention of the fact that governments don't operate according to idealized models of efficiency, it is uncommon for a significant amount of time to be devoted to "government failure," which makes it simple for students to believe that government intervention is the solution to these almost invariably present shortcomings of markets.

The Apologists for Environmental Regulation

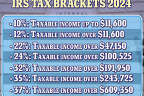

Monopoly theory flaws and common misconceptions about public goods have already been discussed in other places. Externalities, which are often environmental issues, have proven to be one of the hardest hurdles for students seeking to comprehend markets and government to overcome, in my experience. Government intervention isn't necessary for pollution issues, right?A few graphics illustrating the distinction between private costs (or benefits) and social costs (or benefits) are typically included in the externalities section. With the marginal private cost (MPC), marginal social cost (MSC), and marginal private benefit (MPB), the diagram for negative externalities often resembles figure 1. Students are then instructed to compare the optimal quantity of output (Q*) with the quantity of output produced on the market (QM) for the good that causes the negative externality. Any production above Q* results in a net loss known as "deadweight loss," when costs outweigh benefits. The existence of this deadweight loss is taken as proof of market failure, and the writers typically move on to consider various strategies for getting the government to influence the market in the direction of Q*.

Figure 1: The difference between costs and benefits of the quantity of output resulting in negative externalities

Government interventions typically take three forms: (1) command-and-control regulation, (2) emissions taxes, and (3) cap-and-trade (tradable permit) systems. This is because court-made law to resolve conflicts over annoyances like pollution has been viewed as inadequate to deal with externalities.

Many economists dislike command-and-control regulation because it has a propensity to impose expensive and rigid requirements for carbon reductions. It is also particularly prone to "crony capitalism," as business lobbyists can influence regulatory agencies to impose technologies that exclude rivals. Emissions taxes and tradeable permits are far more appealing to economists.

As a component of climate policy, emissions taxes—also known as Pigovian taxes after the Cambridge economist and Alfred Marshall pupil Arthur Cecil Pigou—have attracted more attention. In recent years, numerous suggestions for a federal carbon tax have surfaced, including the "Green New Deal," and even individuals who identify as libertarians have put out such ideas. In particular, the Environmental Protection Agency's Acid Rain Program, which started auctioning off sulfur dioxide licenses in 1993, introduced tradable permit systems to the US. Since the permits trade in a market, tradable permit systems appear to be appealing to market-friendly economists. Regulators control the supply of permits, therefore it's only really a quasi-market.

The majority of economists appear to prefer either of these policies. However, there are serious issues with both carbon taxes and tradable permit programs.

The Pollution Calculation Problem

First, there is no mechanism for the government to calculate the costs associated with pollution, either to impose a tax or set an emission restriction. According to the model in figure 1, it is impossible to locate the MSC, which means that neither the government nor a tradable permit system will be able to determine how much tax to impose.

This calculation problem has long been recognized. James Buchanan explained the problem in Cost and Choice:

According to Art Carden, who stated it bluntly, "The knowledge needed to know whether a certain law 'works' quite literally does not exist, and the main distinction between enterprises and governments is that firms... have market testing for their judgments. The government doesn't.Consider, first, the determination of the amount of the corrective tax that is to be imposed. This amount should equal the external costs that others than the decision-maker suffer as a consequence of decision. These costs are experienced by persons who may evaluate their own resultant utility losses. . . . In order to estimate the size of the corrective tax, however, some objective measurement must be placed on these external costs. But the analyst has no benchmark from which plausible estimates can be made. Since the persons who bear these “costs”—those who are externally affected—do not participate in the choice that generates the “costs,” there is simply no means of determining, even indirectly, the value that they place on the utility loss that might be avoided.

However, economists and decision-makers continue to act as though they have access to the essential knowledge or that the issue can be safely ignored. In 1972, William Baumol acknowledged the information gaps while defending Pigovian taxes in the esteemed American Economic Review:

He said later that "we do not know how to calculate the required taxes and subsidies and we do not know how to approximate them by trial and error."Despite the validity in principle of the tax-subsidy approach of the Pigouvian tradition, in practice it suffers from serious difficulties. For we do not know how to estimate the magnitudes of the social costs, the data needed to implement the Pigouvian tax-subsidy proposals. For example, a very substantial proportion of the cost of pollution is psychic; and even if we knew how to evaluate the psychic cost to some one individual we seem to have little hope of dealing with effects so widely diffused through the population.

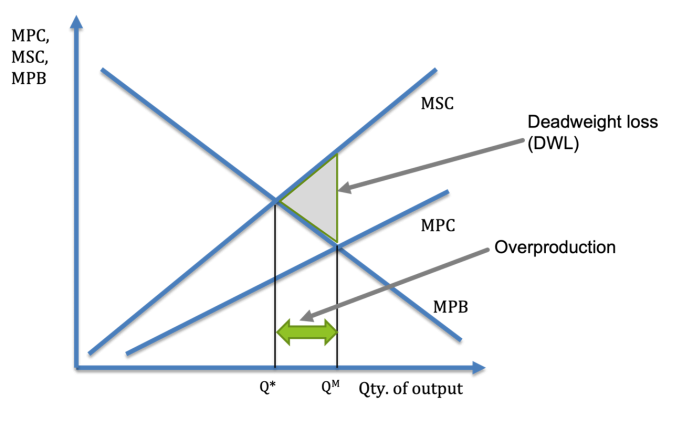

Unfortunately, Baumol mostly ignored these issues and suggested acting "on the basis of a set of minimum standards of acceptability," locating "some maximal level of this pollutant that is considered satisfactory." Of course, this ignores the information issue (how much is "acceptable" or "satisfactory"), which he was aware of. However, Baumol said that "if we allow councils of perfection to paralyze us, we may have even greater cause for regret." In other words, it is preferable to take action to minimize pollution than to impose absolutely no pollution limits. Baumol, and those who continue to support emissions taxes or tradable permits, fail to recognize that, even within their own flawed analytical framework, it is simple to overestimate the MSC and subsequently "overcorrect" with taxes or emissions caps that are too high or low, resulting in an increase rather than a decrease in the deadweight loss triangle (see figure 2). Additionally, they do not recognize how effective tort and nuisance legislation is at stopping environmental violations. In his renowned 1982 essay "Law, Property Rights, and Air Pollution," Murray Rothbard emphasized the importance of this decentralized, court-based system (the common law).

Figure 2: The effects on the quantity of output of overshooting taxes on negative externalities

Environmental (In)Justice

The second significant issue is that neither emissions levies nor tradeable permits have a clear method of making up for the losses that pollution victims continue to endure. Fines or permit auction proceeds go to the government, not the people who have to live with the pollution. The neighbors of polluters' property rights haven't been adequately protected by the authoritarian environmental law apparatus that has evolved over many years, whether through command-and-control or another sort of regulation. Scrubber requirements for coal-fired power plants or sulfur dioxide taxes have little effect on compensating those who may still suffer harm from the remaining emissions. Additionally, if polluters in various areas trade emissions licenses under tradable permit systems, the pollutants will transfer from one polluter's neighbors to another's without payment to these pollution victims. It would seem that justice would require the company buying the licenses to pay out more to its neighbors in proportion to the more pollution they will be exposed to, while the company selling the permits would pay out less to their neighbors. Therefore, if property rights are preserved, the company obtaining permits would receive payment from the company issuing the permits since the acquirer is taking on the responsibility of making amends to its neighbors. However, systems that allow trading in emissions permits have the opposite effect: the company buying the permits pays the company issuing them. The benefits to some observers and the costs to others are viewed as unimportant.Despite the serious ethical issues raised by this, the majority of orthodox economists appear willing to disregard them in favor of pursuing the elusive ideal of "social efficiency." Even if the idea of social efficiency were useful, as Murray Rothbard noted in "Law, Property Rights, and Air Pollution," it still doesn't explain why it should take precedence over all other factors when establishing legal principles or why externalities should be internalized. Similar to this, Robert McGee and Walter Block contend that tradable emissions permits, despite having some efficiency advantages over command-and-control regulation, "entail a fundamental and pervasive violation of property rights" and that this type of "market socialism" should be replaced with the aforementioned court-made common law that strictly protects these rights.

Who Cares about Efficiency?

It is unclear why we should anticipate that government will work toward the most efficient result, even if we set aside the information problem and the ethical dilemma. Each has its own goals; normally, politicians want to be elected, while bureaucrats seek bigger money to work with. Politicians will gladly dismiss anything their economics professors taught them about marginal social cost when under constant pressure from lobbying groups that don't much care about overall economic efficiency. Even if we knew what Q* was, environmentalist organizations wouldn't be likely to stop requesting emissions reductions once it was met. Carbon prices should be high enough to hurt coal companies, but not so high that they force electric utilities to switch to nuclear power, say natural gas producers. In such a setting of conflicting interest groups, the Q* textbook result would only sometimes occur by accident.

We would do well, then, to discard “efficiency-based” theories that make impossible demands for information and that rely on selflessness from government policy makers. As Ed Stringham and Mark White pointed out, following Murray Rothbard:

In addition to the several issues I've already outlined, emissions levies and tradable permit programs also have other issues. For instance, according to research by Bob Murphy, even a carbon tax that is "revenue-neutral" will "likely... [to] impose more deadweight loss on the economy, offsetting at least some of the potential environmental benefits." Carbon taxes will harm economic progress, and calls for such a tax—which is, after all, a tax on capital—are rife with false assertions. We may also know even less about the capabilities and priorities of these remote descendants of ours because many of these proposals are meant to avert harm that could hypothetically occur in the distant future. Furthermore, the costs may increase generations before these potential benefits manifest.Utilitarian theories in general suffer from these calculation problems, but deontological theories, such as rights-based ethical systems, do not. In such theories, legal decisions would be made based on notions of justice rather than efficiency, and judges would not face the unenviable task of calculating the economic consequences, in all possible states of the world, of all their possible actions.

Emissions taxes and tradable emissions permits promise to improve market outcomes, but government cannot do so and may even make things worse. As we've shown, the government lacks the knowledge necessary to determine the minimum amount of pollution that would be acceptable for a given civilization, and officials aren't incentivized to care much about efficiency anyhow. It is more morally and practically acceptable to deal with environmental spillover effects on the basis of rights rather than an illogical "social efficiency." Restoring protections for property rights and lowering pollution issues would benefit greatly from a renewed appreciation for liberty and the common law.