Anticapitalists say that capitalism must create food shortages in order to make money. But economist Jeremy Horpedahl says that this is a silly idea. He showed an image from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) that showed a big drop in how much people spent on food as a share of their income, from 44 percent in 1901 to just 9 percent in 2021. This is something to be happy about, and it's likely because there are so many market countries.

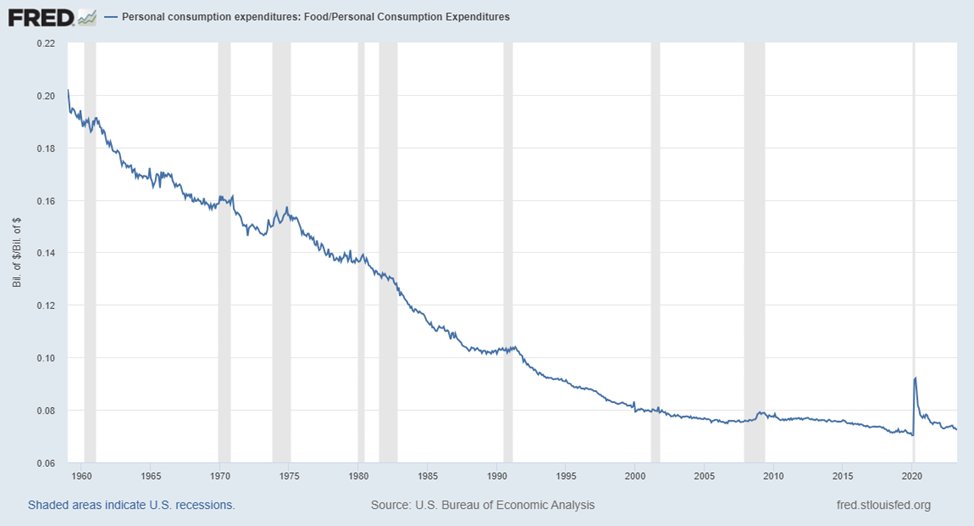

But when Jordan Peterson asked, "And what's happened in the last two years?" I went digging. First, I agreed with what Horpedahl said: the amount we spend on food as a share of our spending has dropped by a huge amount. Second, I saw what Peterson alluded to: a big jump in food spending when covid and the mess of government actions that came with it hit (figure 1).

Figure 1: Food and personal consumption expenditures, 1959–2023

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis, FRED.

The spike looks like a blip, which is interesting. If you didn't know what happened in the last few years, you might look at this picture and say, "Yeah, something strange happened in 2020, but it looks like everything is back to normal." I'm sure, though, that no one has ever seen anything like this. No one would say that going to a restaurant or the food store costs the same today as it did in 2019.What was different in 2020? What's wrong with this graph? Assuming that the Bureau of Economic Analysis data isn't completely wrong (and it's important to be skeptical of government data), why would a January 2023 report on consumer inflation sentiment say that "there is a disconnect between the inflation data reported by the government and what consumers say they now pay for necessities"?

The difference is in the quality of what we as customers get out of it. The amount of money spent may have gone back to where it was before, but that's not the whole story. "Shrinkflation" and "skimpflation" have hurt the amount and quality of the food we like, or maybe it's more accurate to say the food we accept.

Businesses know that raising prices isn't popular, especially when many customers think that greed is driving up costs. So, businesses cut costs by putting less food in the package, watering down the product but keeping the same amount, or finding other ways to save money that customers might not notice right away.

Some of these cases are recorded on websites like mouseprint.org, which is good news: Sara Lee blueberry bagels reduced from 1 lb., 4.0 oz. per bag to 1 lb., 0.7 oz. Bounty “double rolls” reduced from 98 sheets to 90 (how is it still a “double roll”?) Gain laundry detergent containers reduced from 92 fl. oz. to 88 fl. oz. without any obvious difference in the size of the container Dawn dish soap bottles reduced from 19.4 fl. oz. to 18.0 fl. oz. Green Giant frozen broccoli and cheese sauce packages reduced from 10.0 oz. to 8.0 oz. with no change in the advertised number of servings per package In some cases of skimpflation, the size or weight of a product stays the same, but the amount of each ingredient changes. For example, Hungry-Man Double Chicken Bowls, a frozen meal with fried chicken and macaroni and cheese, kept the same net weight of 15.0 oz, but the amount of protein dropped from 39 grams to 33 grams.

Even though businesses are cutting back on the amount and quality of food they sell, people are also buying less food and even lower-quality food. The Consumer Inflation Sentiment Report from January 2023 says that 69.4% of the people who filled out the survey "cut back on the quantity, quality, or both of their grocery purchases in the last 12 months because of rising prices."

We have also seen a big, long-term change in how businesses treat their customers. For a few months or even a few years, many places stopped serving food to eat in. Even though some places have brought back the option to eat in, the service hasn't been quite the same, with QR-code menus, shorter hours, less staff, and more curt attitudes.

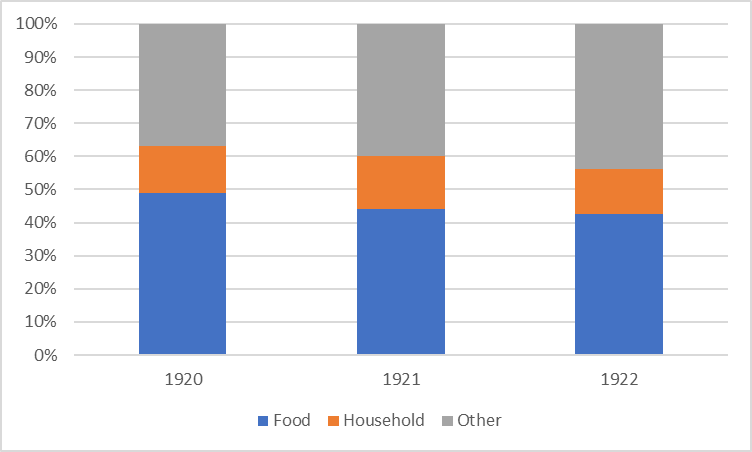

It's not surprising that the government's massive actions, like making trillions of dollars, would have a lot of effects, some of which show up in data and many of which don't. For example, if we look back at the time of German hyperinflation, we find that the statistics on how much people spent on food (figure 2) is surprisingly boring.

Figure 2: Household expenditures in Germany, 1920–22

Source: Data from Carl-Ludwig Holtfrerich, The German Inflation, 1914–1923: Causes and Effects in International Perspective, trans. Theo Balderston (New York: Walter de Gruyter, 1986), cited in Gerald D. Feldman, The Great Disorder: Politics, Economics, and Society in the German Inflation 1914–1924 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), p. 549.

Even though prices went through the roof, there wasn't much change in how much was spent. During the same time period, the food price index went up by 14,613%. Prices for everything, not just food, were going up very quickly, so the amounts spent in each category stayed pretty much the same.Gerald D. Feldman, a historian, said something that sounds familiar about the German household spending data: "As one study after another pointed out, however, the full impact of these changes had to be understood in qualitative terms." There were changes in "the quality and quantity of the food eaten" and "the quality of the clothes worn," among other things.

These differences are too small for government data to show. This should be obvious: your personal experience as a customer is more than just the price you pay for a certain amount of food. We're not just tools, so we don't talk about how we live in terms of miles per gallon or kilowatt hours.

This is why Ludwig von Mises criticized aggregates and indexes that claimed to measure different parts of customers' lives: "The pretentious solemnity with which statisticians and statistical offices calculate indexes of purchasing power and cost of living is out of place. These index numbers are, at best, rough and not very exact ways to show how things have changed.

In the end, he says, "A wise housewife knows much more about how changes in prices affect her own family than the averages can show."