To help pay down the EU's accumulated debt from funding the post-pandemic economic recovery, the EU is considering implementing a new wealth tax on its member states. Most European Union member states have done away with their net wealth taxes over the past three decades because of the harm they did to long-term economic growth, innovation, and entrepreneurship.

In a petition sent to the European Commission last month, European citizens' initiative (ECI) supporters collected the requisite seven signatures to demand that lawmakers explore imposing a wealth tax on the European Union's richest earners. The petitioners have a year from the time the ECI is registered to get one million signatures. The European Commission would then review the proposal and provide an official response in the form of new regulations, but it is under no obligation to do so.

The effort was started by a discussion on wealth tax options at an EU Tax Observatory panel.

During the panel, various problems with the system as it currently stands were brought up. Professor of economics at the University of Zurich Florian Scheuer remarked that "many more people than only the very wealthy pay it" due to Switzerland's net wealth tax's low thresholds. EU Tax Observatory director Gabriel Zucman argued that wealth taxes "dramatically fail" to tax the wealthy because they do not sufficiently include financial assets. However, some have pointed out the "relatively high administrative burden due to the necessity of regular assessments of the tax base" and the difficulties of imposing a wealth tax at the national level due to "capital becoming increasingly mobile."

Research fellow at Oxford University's Centre on Business Taxation Kristoffer Berg believes that "in settings with large unrealized capital gains," wealth taxes can push the wealthy to cash in. For this reason, the wealth tax should be minimal and applied to all forms of wealth and income. Furthermore, an Oxfam tax policy advisor emphasized the need to "focus on the very richest" while developing these levies.

Little data on the present trends in wealth taxes among industrialized nations has been included in these talks about a potential EU wealth tax. This EU proposal can be better understood in light of those tendencies and the existing condition of wealth taxation in OECD countries.

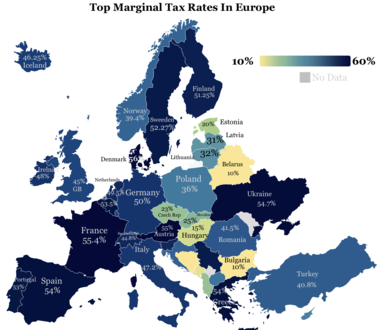

As governments become more aware of the economic problems inherent to such taxes, the number of OECD nations that have imposed net wealth taxes has decreased from 13 in 1965 to 4 in 2023: Colombia, Norway, Spain, and Switzerland. According to OECD data, in 2021, Colombia, France (currently a real estate tax), Norway, Spain, and Switzerland were the top five nations in terms of income received via net wealth taxes on individuals. In 2021, net wealth taxation accounted for only 1.2% of total revenues from these five nations on average, compared to 4.03 % in Switzerland, 0.92 % in Norway, 0.51 % in Spain, 0.45 % in Colombia, and 0.18 % in France.

An OECD analysis found that high wealth taxes discouraged innovation and stunted long-term economic growth by discouraging risk-taking by business owners. Investment and risk-taking might be encouraged by net wealth taxes, the paper adds. The basic idea is that a wealth tax would reduce an entrepreneur's after-tax return, encouraging them to take on even riskier initiatives in order to increase their total possible return. However, a wealth tax is not an effective tool for encouraging risk-taking, as the wealthy may simply increase their spending to offset the tax.

A new research describes an alternative method by which wealth taxes affect the financial policies of corporations. The research concludes that dividend payments rise sharply in the presence of individual wealth taxes and a rise in stock prices. The prevalence of this trend is greatest in privately held businesses. When stock prices rise to the point that controlling shareholders' wealth tax liability increases significantly, those shareholders might pressure corporations into paying out a dividend. It has been found that higher dividends result in less investing activity.

The economic impact of net wealth taxes has led to their repeal in many countries over the years. Finance Minister Bruno LeMaire of France has stated categorically that the wealth tax repeal was implemented as part of a reform package to "attract more foreign investment." A decrease in the corporate tax rate was also part of the French reform package and has been phased in over time.

Recent developments in Europe's wealth tax have prompted regional governments in Spain to challenge a new "solidarity wealth tax" in the country's highest court, while billionaires in Norway have prompted the approval of a higher exit tax. A tax analyst from the Norwegian think group Civita echoed the argument that wealth taxes influence company decisions by saying, "it forces owners to ask their companies for dividends, sometimes bigger than profits." It makes people much less likely to put money into businesses. Additionally, a "solidarity" fee on Swiss citizens with assets over 3 million francs ($3.4 million) was recently voted down by voters in Geneva. The mayor and city council had both publicly opposed the price hike.

Perhaps European countries should abolish wealth taxes rather than enact a continental one because they raise so little money while potentially discouraging business creation and investment.