The Fed told Congress to let the debt grow twice as fast as the economy.

At the time of this writing, the federal government’s debt is $33 trillion and rising.[1] Earlier this year, after a protracted negotiation and just days before the federal government was expected to become unable to pay its obligations, President Biden and House Speaker McCarthy reached a deal to suspend the debt ceiling until January 1, 2025, as part of the Fiscal Responsibility Act (FRA) of 2023.[2] The deal imposes temporary caps on certain types of government spending, reducing projected budget deficits by about $1.5 trillion over the next decade.[3]

Even after the FRA, the latest forecast from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) indicates that federal budget deficits will grow substantially over the next decade and with it the national debt. Through 2033, deficits will total $18.8 trillion, reaching an annual budget deficit of $2.7 trillion in 2033, or 6.4 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), as spending growth outpaces revenue growth.[4] Debt held by the public will rise steadily from 97 percent of GDP in 2022 to 115 percent in 2033—the highest level on record.

These forecasts and other concerns about the sustainability of the federal debt led Fitch Ratings to downgrade U.S. debt from AAA to AA+ on August 1, noting “expected fiscal deterioration over the next three years, a high and growing general government debt burden, and the erosion of governance relative to ‘AA’ and ‘AAA’ rated peers over the last two decades that has manifested in repeated debt limit standoffs and last-minute resolutions.”[5] Fitch expects the deficit to reach 6.3 percent of GDP this year and rise from there due to weak economic growth and an interest burden that will grow to 10 percent of revenue by 2025.

According to the latest monthly budget review from the CBO, the deficit in the first 10 months of FY 2023 is $1.6 trillion, more than twice the deficit over the same period last year.[6] Spending is up 10 percent, driven in part by the rising costs of Social Security, Medicare, interest on the debt, and Pres. Biden’s new income-driven repayment plan for student loans. At the same time, tax collections are down 10 percent, due in part to lower capital gains tax collections as the stock and housing markets have deflated.

Excluding the effects of President Biden’s student loan cancellation policy (which the Supreme Court struck down in June and is distinct from the administration’s income-driven repayment plan), budget experts are forecasting a doubling of the deficit this year, from $1 trillion (or 4 percent of GDP) last year to $2 trillion (or about 8 percent of GDP) this year. Economist Jason Furman and other experts note such a growing deficit pattern is essentially unprecedented in U.S. history outside of major crises and economic downturns.[7]

The current track of ever-increasing budget deficits, interest costs, and debt is not sustainable. In this paper, we discuss how the U.S. debt burden compares to the burdens in other countries and how other countries have successfully reduced their debt in the past. We then analyze the FRA and discuss how lawmakers could build on FRA’s reforms to stabilize the U.S. fiscal trajectory.

U.S. Federal Debt in Context

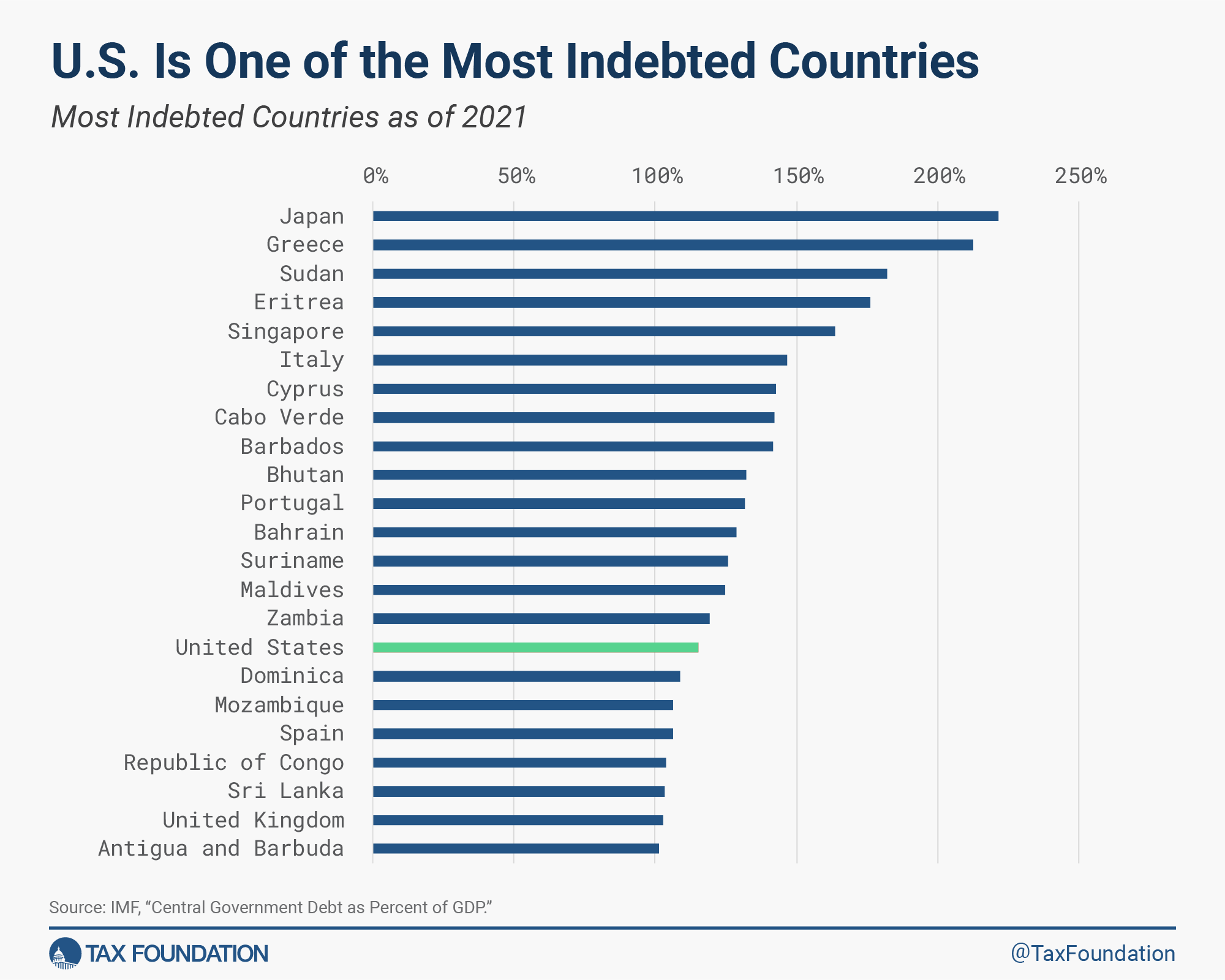

According to the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) measure of central government debt, the U.S. federal government is among the most indebted governments in the world.[8] As of 2021 (the latest available data), federal debt reached 115 percent of GDP, ranking 16th highest out of 164 countries for which the IMF has data. Japan tops the ranking with central government debt of 221 percent of GDP, followed by Greece, Sudan, Eritrea, and Singapore. Not long ago, the U.S. was among the least indebted countries. In 2001, U.S. federal debt was 42 percent of GDP, lower than debt levels found in 100 other countries.

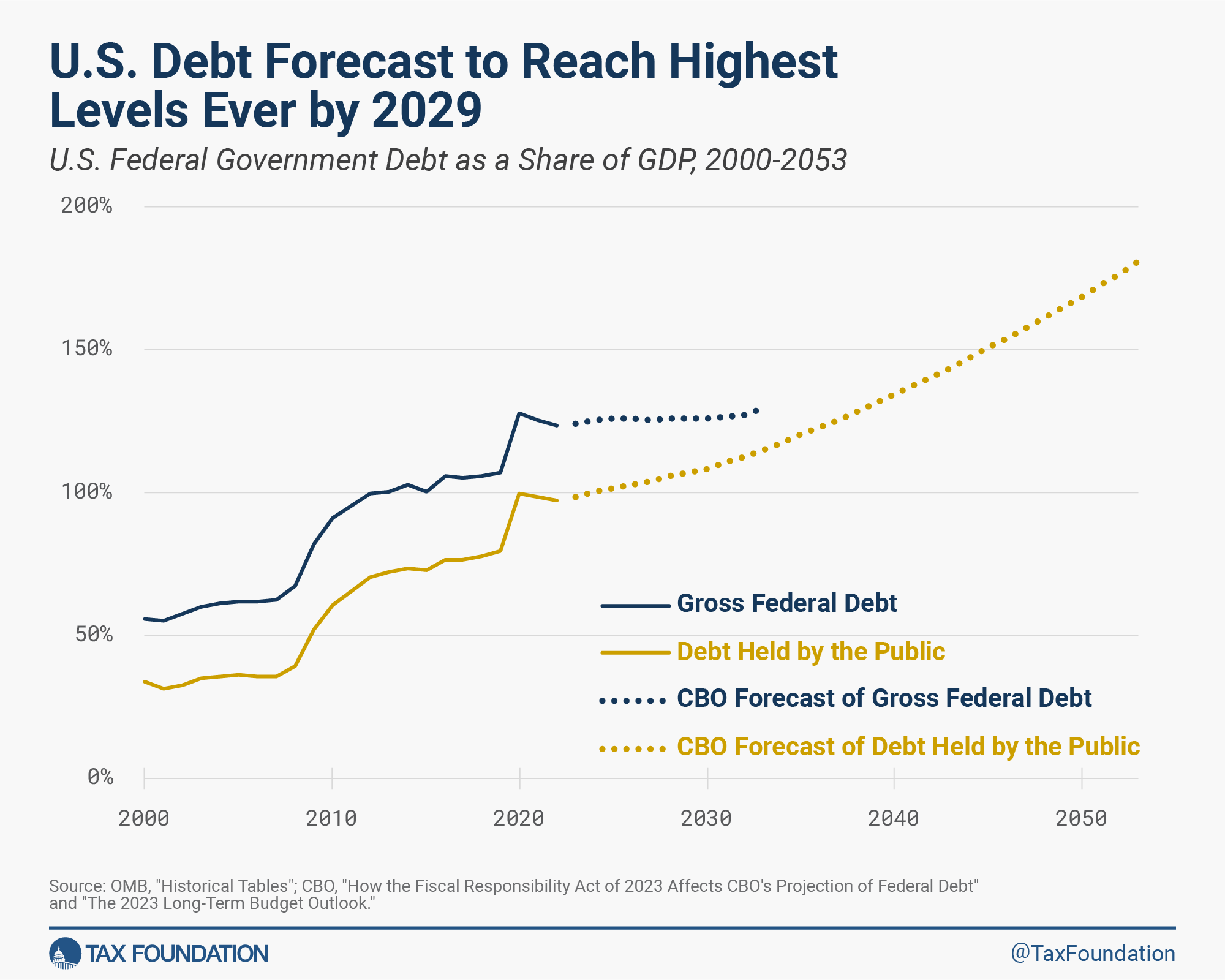

As illustrated in the nearby chart, using historical data from the White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB),[9] U.S. debt surged upward in two stages over the last 20 years, first after the financial crisis in 2008 and then after the COVID-19 pandemic[10] that began in 2020.[11] Gross federal debt climbed to a record high of 128 percent of GDP in 2020 before falling to 123 percent in 2022. The recent downtick was primarily due to a surge in inflation as well as real economic growth coming out of the pandemic, factors that temporarily reduced debt burdens in many countries.[12]

Debt is forecasted to reach unprecedented levels in the coming years. The CBO projects debt held by the public as a share of GDP will climb from 97 percent in 2022 to 115 percent in 2033—reaching the highest level on record by 2029—before climbing further to 180.6 percent by 2053.[13] The increase is mainly due to population aging and the rising costs of Social Security and Medicare and assumes no major economic calamities or changes in federal laws will occur.[14]

And yet, the problem may be even worse. Mark Warshawsky and other researchers at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) see rising health-care costs and interest rates contributing to even higher levels of debt.[15] They forecast debt held by the public will grow to 136 percent in 2032 and 264 percent in 2052. Like the CBO forecast, theirs assumes no banking crisis, war, pandemic, or other emergency that might cause a major economic downturn and spike in deficits. As it is, the AEI researchers forecast annual deficits to reach 7 percent of GDP by 2030 and escalate rapidly thereafter in an unprecedented and unsustainable path, around the same time that the Social Security and Medicare trust funds are expected to be depleted.

All of this may seem far off, but the costs of high debt levels are upon us now. They are most clearly visible in the form of high inflation, high interest rates, and slowing economic growth.[16] As John Cochrane,[17] Eric Leeper,[18] Tom Sargent,[19] and other economists[20] have described, the extraordinary surge of federal spending during the pandemic—exceeding $5 trillion through early 2021, or 27 percent of GDP—kicked off a 40-year high in inflation.[21]

That is because the increased spending was not financed by tax increases; it was financed by debt purchased by the Federal Reserve through money creation.[22] To combat high inflation, the Federal Reserve has raised interest rates to the highest levels in more than 20 years. That brute force method of slowing the economy through higher borrowing costs has thus far led to heavy losses for investors, a collapse in home sales, and several bank failures, among other signs of distress, with more pain to come as debt of various types is rolled over at higher interest rates.[23]

High interest rates are also putting pressure on the federal budget, causing interest payments on the debt to crowd out other federal priorities and limiting the federal government’s ability to respond to future crises. According to the CBO, the federal government’s net interest cost will exceed $1 trillion annually by 2029, eclipsing the defense budget.

The financial stress and instability of high interest rates are spreading around the globe, leading the IMF[24] to recommend fiscal restraint as a less economically damaging way to reduce inflation and debt.[25]

How Other Countries Successfully Reduced Debt and Deficits

As U.S. lawmakers consider options to address the underlying gap between spending and revenue going forward, they should draw on international experiences of fiscal consolidation.[26] International experience cautions against tax-based fiscal consolidations, but modest tax increases may be part of a successful debt reduction package.[27] Overall, a rough guideline that emerges is that deficit reduction efforts should primarily be focused on spending reduction, with 60 percent or more of a plan’s savings coming from spending cuts and 40 percent or less from revenue increases. Further, the types of spending cuts and tax reforms that are part of a fiscal consolidation also matter.

In a recent survey of studies on the experience of countries around the world dealing with fiscal deficits and debt, the IMF outlines factors that contribute to sustained improvements in deficits and debt-to-GDP levels.[28] Reductions in social spending, as opposed to public investment, tend to produce more lasting fiscal improvements, as do less distortionary tax increases—including higher consumption, property, excise, and environmental taxes as well as reductions in tax expenditures.

Other factors important for success include the public’s perception that the government will actually fulfill its commitments and that the adjustment will be gradual, not “front-loaded” with large structural policy changes.

Additional research further supports the idea that fiscal consolidations based on spending cuts have had fewer negative effects on GDP than tax increases. Looking at 16 OECD countries over a 30-year period, Alberto Alesina and his coauthors found that, on average, spending cuts were associated with mild recessions and in some cases no downturns at all, while almost all fiscal reforms based on tax increases were followed by “prolonged and deep recessions.”[29] Fiscal adjustments based on tax increases reduced investment and business confidence. By contrast, business confidence rebounded almost immediately after a fiscal adjustment based on spending reforms.

In a follow-up paper, Alesina and his coauthors showed that cuts in transfer spending had milder negative effects on economic growth, nearing zero, compared to cuts in government consumption and investment, though both have relatively little impact on growth compared to tax increases.[30]

Examining fiscal adjustments from a sample of 26 countries from 1995 to 2018, a Mercatus Center analysis found that successful consolidations, defined as one where the debt-to-GDP ratio declines by at least 5 percentage points in the three years after the plan is implemented, were more spending-focused than tax-focused.[31] More than half (53 percent) of expenditure-based fiscal consolidations, defined as those in which spending cuts represent 60 percent or more of deficit reduction, were successful. In contrast, only 38 percent of tax-based fiscal consolidations (defined as those in which tax increases represent 60 percent or more of deficit reduction) were successful. Balanced fiscal consolidations, however, had the highest success rate at 55 percent. Among the successful fiscal consolidations, on average, 60 percent of the deficit reduction came from spending cuts, whereas among the unsuccessful fiscal consolidations, 74 percent of the deficit reduction came from tax increases.

A European Central Bank analysis arrived at a similar conclusion: EU countries that pursued spending-based consolidations had higher growth rates five years following a fiscal consolidation announcement than those that pursued tax-based ones.[32] While part of the difference in economic performance can be explained by better follow-through for revenue-based plans, the bulk of the difference was due to the composition of consolidations, with revenue having large, negative effects compared to nearly zero for spending.

When it comes to designing tax changes, raising a dollar of revenue through different taxes has different effects on the economy. A more harmful tax increase can shrink the economy, yielding less revenue from other taxes. Harm the economy too much and the solution may prove counterproductive, reducing the likelihood of successful debt stabilization.

In a study of 17 OECD countries over a 30-year period, Norman Gemmell and other academics showed that reducing deficits by raising distortionary taxes, such as income taxes, consistently reduced economic growth, while raising less distortionary taxes, such as consumption taxes, was more growth-enhancing.[33] They found small positive growth effects from deficit-financed “productive” spending, such as infrastructure, implying that cutting such spending could hurt growth. Negative growth effects from cutting productive spending would take longer to materialize, while negative effects of tax increases would be more immediate. Deficit-financed “nonproductive” spending, such as transfers, was shown to have a negative effect on long-run economic growth, suggesting that cutting them would boost growth.

In all, the experience with successful fiscal consolidations suggests adjustments should be gradual and focused on spending, with careful consideration of the growth effects of selected policies. If tax increases are included in a package,[34] it is most effective to focus on less distortionary taxes, such as consumption taxes, or tax reforms that rationalize tax expenditures[35] and broaden the tax base.[36]

How the Debt Ceiling Deal Affects the U.S. Budget

Among other changes, the debt ceiling deal enacted in June (FRA) limits discretionary spending over the next two years, expedites permitting for pipelines and other energy infrastructure, and expands work requirements for food and income assistance programs.[37]

Specifically, the deal caps discretionary spending (except for certain funding including emergencies and overseas contingencies) at $1.59 trillion in FY 2024 and $1.61 trillion in FY 2025, roughly flat relative to this year’s $1.63 trillion. It caps defense spending at $886 billion in FY 2024 and $895 billion in FY 2025 and non-defense discretionary spending at $704 billion in FY 2024 and $711 billion in FY 2025.

The deal also contains a mechanism to enforce a better budget process by further reducing the budget caps by 1 percent if Congress fails to enact all 12 appropriations bills by January 2024. Additionally, the deal specifies certain unenforceable spending limits beyond FY 2025.

Outside of the spending caps, the deal makes several other changes with relatively small effects on the budget. The deal rescinds about $11 billion in unspent pandemic relief funds, codifies the already-expected end of the pause in student loan payments, and claws back about a quarter of the $80 billion in additional IRS funding authorized by last year’s Inflation Reduction Act. The deal also tightens work requirements and eligibility rules for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF), speeds the permitting process for energy and infrastructure projects by limiting environmental reviews, and requires cost estimates for administrative actions through 2024.

In total, the CBO estimates the FRA will reduce deficits by $1.5 trillion from 2023 to 2033, including a substantial reduction in interest payments on the debt of $188 billion.[38]

The FRA rightly focuses on reducing spending, which is what most successful fiscal consolidations have done. But while the spending reductions are substantial, they pale in comparison to total federal spending of about $6.4 trillion this year and $79 trillion projected over the next decade, or projected deficits of about $19 trillion over the next decade.[39]

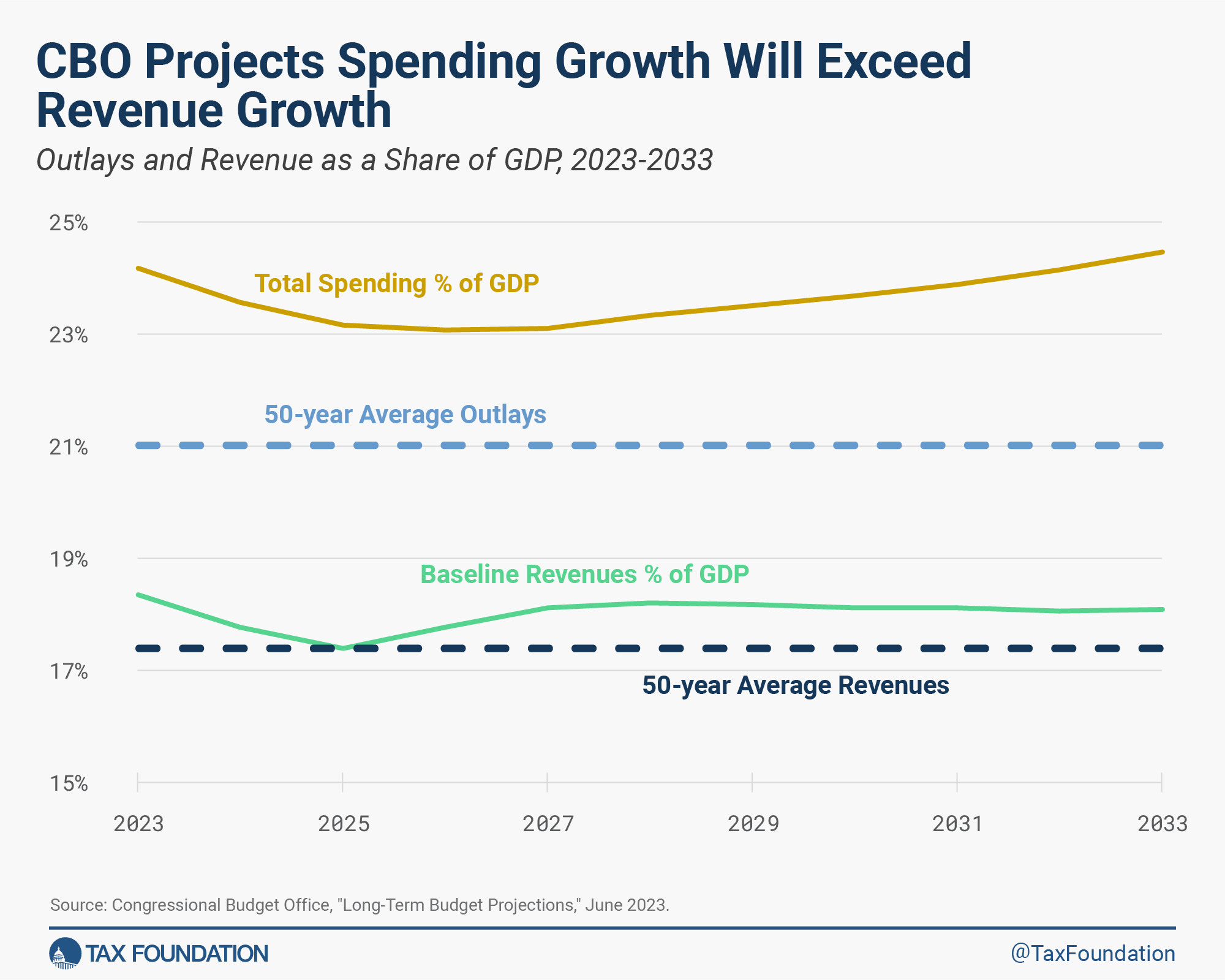

The current CBO forecast indicates spending this year will be about 24.2 percent of GDP and average 23.6 percent of GDP over the next decade, compared to an average of 21 percent over the last 50 years. To bring spending closer into alignment with historic norms would require cuts several times larger than what the FRA enacted. Just to stabilize the debt at its current share of the economy would require about $7.5 trillion in deficit reduction over the next 10 years, inclusive of reduced interest costs.

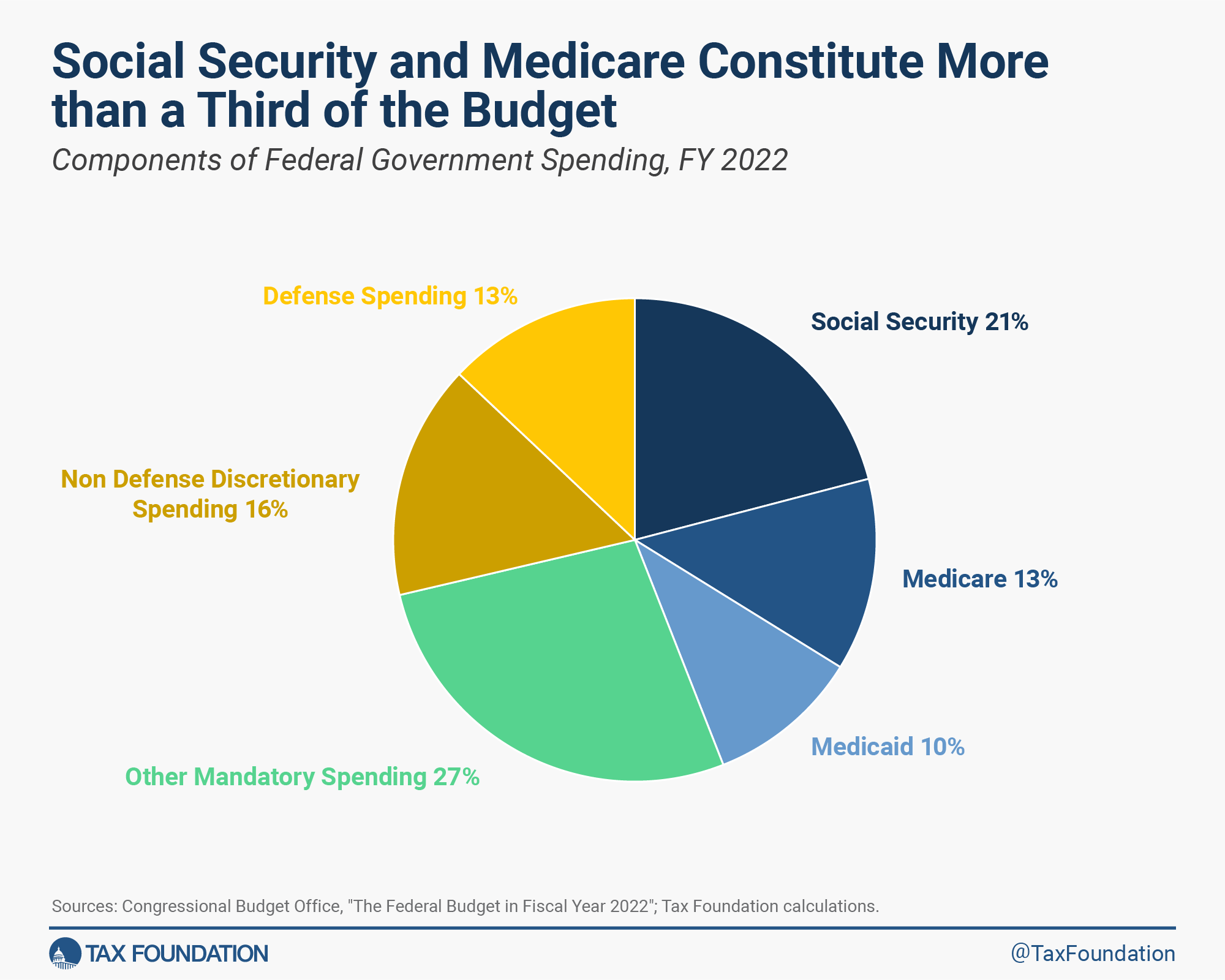

The problem is that the FRA does not address the largest part of the budget and the source of growing fiscal imbalances, which is mandatory spending, including major entitlement programs such as Social Security and Medicare.[40] Under current law, mandatory spending is set to grow from 14.3 percent of GDP next year to 15.3 percent in 2033, while discretionary spending (the part of the budget addressed by the FRA) will shrink from 6.6 percent to 5.6 percent over the same period.[41] Discretionary spending was already on a downward trajectory before the FRA; in May, the CBO forecasted it would fall from 6.5 percent of GDP in 2024 to 6.0 percent in 2033.[42]

By leaving mandatory spending on autopilot, the FRA fails to address the core driver of long-term deficits and fails to grapple with the weakening finances of the Social Security and Medicare trust funds, which are projected to be insolvent within a decade.[43]

To address the more challenging parts of the budget, especially the unsustainable growth in mandatory spending, lawmakers should follow up on the debt ceiling agreement with a focus on long-term fiscal sustainability.

Options for Reform

A Fiscal Commission and Other Reforms to the Budget Process

In the aftermath of the FRA, Speaker McCarthy indicated he would seek to convene a fiscal commission to grapple with long-term budgetary challenges, a meaningful next step to improve the process of budget reform.[44] The 2010 Simpson-Bowles Commission was the last time a fiscal commission was assembled, and it can offer some lessons going forward.[45]

First, perhaps now more than ever, convening a fiscal commission makes eminent sense. A commission comprised of budgetary experts selected on a bipartisan basis would provide a space for tough budget decisions outside of the political pressures that make real discussion of budgetary alternatives and trade-offs impossible. The commission should aim for specific targets, such as stabilizing debt as a share of GDP at or below current levels, and engage and solicit input from citizens and outside experts to form a set of recommendations.

Second, as noted by Dave Walker and others, for a fiscal commission to be successful, it needs to be statutory, so the administration and members of Congress have buy-in to the process.[46] The recommendations of the commission should be put to an up or down vote in Congress. All of this, of course, assumes elected officials first acknowledge the scale of the problem, are willing to engage with solutions, and then follow through with action.

As a longer-term process reform, Dave Walker and others, including the late Nobel laureate economist James Buchanan, have also recommended a constitutional amendment to enforce fiscal sustainability.[47] The amendment could take many forms. Buchanan recommended an amendment that limits estimated spending to estimated tax revenues, with the ability to waive this requirement in extraordinary situations via separate approval by three-fourths of the House of Representatives and the Senate.[48]

Several countries have had success controlling debt through a similar constitutional rule. For instance, since 2003, Switzerland’s “debt brake,” which limits spending to revenues over the business cycle, has led to the stabilization of gross government debt at just over 40 percent of GDP.[49] As with a fiscal commission, the effectiveness of such an amendment depends on a wide consensus among the public and policymakers.[50] The Swiss debt brake, for example, was approved by 85 percent of its public. While this seems a remote possibility currently in the U.S., an amendment process could gain traction as the growing U.S. debt becomes more problematic.

Spending Reforms

Turning to reforms of particular spending programs, lawmakers should focus on controlling the growth of the largest mandatory spending programs: Social Security and Medicare. Together, the two programs will grow from 8.2 percent of GDP this year to 10.1 percent of GDP in 2033, while the rest of the budget shrinks from 15.9 percent to 14.4 percent, according to the CBO’s latest forecast.[51] Over the long run, essentially all of the deficit is due to Social Security, Medicare, and associated interest costs.[52]

The demographic factors contributing to the growth of these old-age programs are not uniquely American, as populations are aging rapidly in several countries,[53] especially in Japan and across Europe. There too, pressure is rising on programs that promise benefits for an expanding pool of retirees financed by taxes on a shrinking pool of workers.[54] Economist Eric Leeper describes this dynamic as creating a kind of “insidious” inflationary pressure, as the budgetary imbalance and associated risks grow somewhat imperceptibly over time and the looming policy uncertainty creates costly maneuvering.[55]

Social Security and traditional Medicare (Part A) are both funded by payroll taxes on a “pay-as-you-go basis.” That is, current payroll taxes paid by today’s workers fund payments to today’s retirees. Unlike discretionary spending, which must be voted on by Congress every year during the appropriations process, current law mandates Social Security and Medicare spending. Mandatory spending in its entirety represents more than two-thirds of the current U.S. budget.[56]

An aging U.S. population and a declining worker-per-retiree ratio (now only 3 to 1) have contributed to the cost of financing Social Security and Medicare. Under current law, Medicare’s Hospital Insurance Trust Fund will be insolvent by 2031, and Social Security’s

Old Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance (OASDI) Trust Fund by 2033.[57] Without reforms, Social Security benefits would be automatically reduced across the board by 20 percent, and Medicare hospital insurance payments would be cut by 11 percent. Absent any reforms, the 2023 Trustees Report shows that a significant payroll tax hike of 4.2 percent would be required to close the current funding gap for OASDI and Medicare.[58]

Given the dire outlook, policymakers must reform the programs to ensure their long-run stability. A brief, non-exhaustive review of various proposals over the past decade to reform Social Security and Medicare illustrates the possibility of tackling the issue with a measured and bipartisan approach.

Social Security Reforms

In 2010, President Obama established the National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform to develop a plan to reduce the deficit. The bipartisan commission produced what became known as the Simpson-Bowles plan—named after then-Senators Alan Simpson (R-WY) and Erskine Bowles (D-NC)—which proposed significant changes to Social Security to ensure its fiscal sustainability.[59] Although the plan was never enacted, many of its recommendations can be found in other proposals, and for this reason, it is worth reviewing in full.

Simpson-Bowles would have slowed benefit growth for high-income earners, making Social Security more progressive. Currently, benefits are calculated using a three-bracket system, where higher earners receive a lower share of their lifetime earnings than lower earners. The plan would have gradually phased in a four-bracket structure of replacement rates starting in 2017, reducing the share of lifetime benefits for higher earners even further.

Additionally, the plan would have gradually raised the retirement age. Under current law, the normal retirement age is 67, but retirees can begin collecting benefits as early as 62. Simpson-Bowles would have indexed both the normal and early retirement ages to life expectancy, making the normal retirement age 68 by 2050.

Currently, all Social Security benefits are adjusted for inflation using the Consumer Price Index for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers (CPI-W). The plan would have switched to chained CPI for cost-of-living adjustments (COLAs) instead. The standard CPI typically overstates inflation as it doesn’t account for consumers’ ability to switch to cheaper substitutes for goods, whereas the chained CPI better captures these consumption dynamics.[60] Switching to the chained CPI would slow benefit growth and therefore reduce the overall cost of the program.

On the revenue side, the plan would have gradually raised the payroll tax cap. Currently, wages and salaries above $160,200 do not face the payroll tax for Social Security.[61] As a result, the tax applies to about 83 percent of all wages earned. Simpson-Bowles would have raised the cap to ensure that 90 percent of all wages were covered by 2050.

Another more recent proposal by Senator Bill Cassidy (R-LA) would attempt to shore up Social Security by borrowing $1.5 trillion and placing it in a diversified investment fund that would be used to replenish the Social Security trust fund.[62] Cassidy characterizes the proposal as a bridge between President Bill Clinton’s proposal to invest part of the trust fund in stocks, and President George W. Bush’s proposal to partially privatize Social Security. However, the plan does not include private accounts, a key feature in successful pension reforms implemented in several countries,[63] including Sweden[64] and Australia.[65] Lawmakers should look to their experiences[66] for guidance on this promising direction for reform.[67]

Medicare Reforms

Currently, physicians who serve patients under traditional Medicare are reimbursed under a fee-for-service system, where they are compensated for the quantity of services they provide rather than the quality. This leads to physicians often providing unnecessary treatments or tests that do little to improve health outcomes for their patients, driving up the costs of Medicare. Proposals to reform fee-for-service have included switching to a system of bundled payments, where physicians are reimbursed based on a fixed price for specific medical episodes.[68] The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services began experimenting with such a system[69] for hip and knee replacements in 2016, and announced further expansions for other types of care, but expanding it even more broadly could help keep costs down.[70]

Alternatively, reforms could go even further by switching to a system of capitation, where physicians are paid a set amount per patient, regardless of how much care is provided. Currently, Medicare Advantage (Medicare Part C) functions this way.[71] Under Medicare Advantage, recipients select among a variety of mostly managed care plans and private insurers receive a fixed payment through Medicare to cover the medical expenses. This incentivizes doctors to serve their patients in the most efficient way possible.

Other proposals call for simply increasing premiums. Premiums for Medicare Part B (which covers outpatient care) currently only cover about 25 percent of the program’s outlays.[72] The CBO estimated that increasing the basic premium to cover 35 percent of the outlays would reduce the deficit by $406 billion from 2023 to 2032.

Similarly, reforming cost sharing would reduce health-care overutilization and lower expenditures. Under the current system, Medicare patients face a high deductible when admitted to a hospital, but no cap on out-of-pocket expenses. As a result, 90 percent of patients acquire additional private coverage known as Medigap.[73] These plans are often expensive because the government is picking up the tab, and only a few plans are available, leading patients to consume more health care than necessary. The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (CFRB) offered a proposal that would implement an out-of-pocket cap and a higher deductible for non-hospital services, reducing the need to purchase additional coverage.[74]

One of the more ambitious plans to reform Medicare is to transition to a “premium support” model. Such a system was proposed by Senators Ron Wyden (D-OR) and Paul Ryan (R-WI) and the Bipartisan Policy Center (BPC) in 2011.[75] The Ryan-Wyden plan would have allowed traditional Medicare plans to compete with private insurance plans in a competitive bidding process, and then the government would have provided vouchers to seniors to purchase coverage.[76] The value of the vouchers would have grown at a rate of GDP plus one percent, and the expectation was that allowing private insurers to compete would help lower costs. To keep costs down even further, the BPC plan would have required Medicare beneficiaries earning above 150 percent of the poverty level to pay higher premiums if spending exceeded the growth limit.

Finally, numerous proposals have been offered to reduce the price of drugs purchased through Medicare. While some of these policies can actually harm innovation in the pharmaceutical sector (e.g., the Inflation Reduction Act’s price controls on specific drugs),[77] more modest reforms could encourage physicians to prescribe cheaper generics.[78] Under Medicare B, doctors purchase drugs for their patients and then get reimbursed based on the average sales price of the drug (net of all rebates and discounts), plus 6 percent of the drug cost. This incentivizes physicians to recommend more expensive, branded drugs since they will receive a larger reimbursement.

One proposed reform from the CFRB would implement “clinically comparable drug pricing,” where physicians would be reimbursed based on a weighted average sales price for clinically similar classes of drugs.[79] This would remove the incentive for physicians to recommend more expensive drugs, as they would incur all the additional costs of purchasing a drug above that weighted average sales price.

Tax Reforms

As discussed above, the experiences of countries around the world caution against raising particularly distortive taxes to reduce debt. However, modest tax increases with minimal harm to the economy can contribute to debt stabilization.

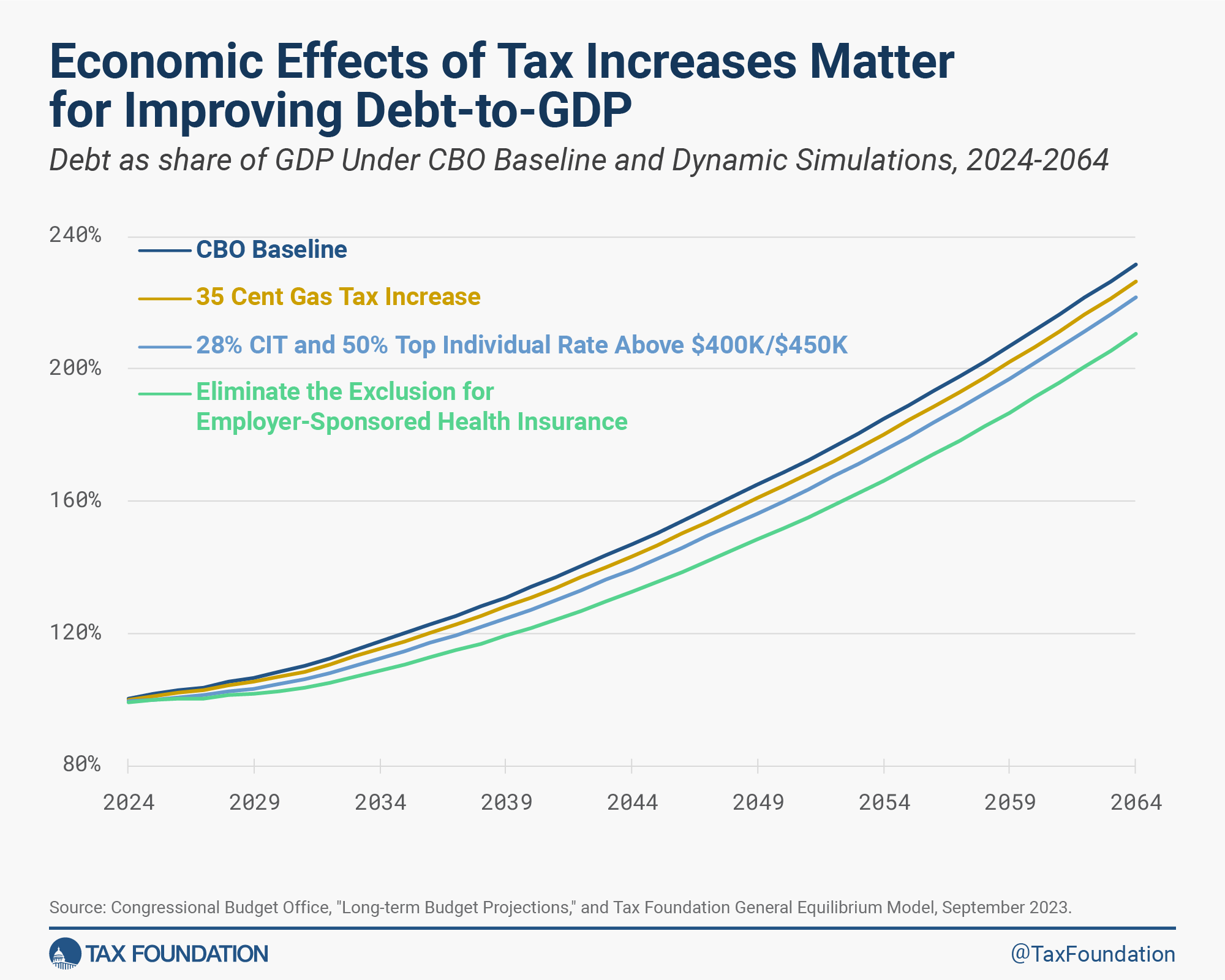

To illustrate, we have simulated the following three potential tax increases that differ considerably in their effects on the U.S. economy and the federal debt burden:

Increasing the federal gas tax by $0.35 and indexing it for inflation Broadening the individual income tax base by eliminating the exclusion for employer-sponsored health insurance (ESI) Raising the top individual income tax rate to 50 percent above $400,000 for single filers and $450,000 for joint filers, and raising the corporate tax rate to 28 percent

As shown in the table and chart below, all three options would raise substantial revenue, in excess of $3 trillion over 10 years in the case of eliminating the ESI exclusion. Both the higher gas tax and the elimination of the ESI exclusion result in relatively minor economic trade-offs for the revenue raised. In contrast, higher marginal income tax rates come at a steep cost: GDP would be reduced by about 1.3 percent over the long run due to decreased incentives to work, save and invest.

As a result, a less economically harmful option like eliminating the ESI exclusion results in a much more powerful reduction in long-run debt as a share of GDP—double the impact on the debt ratio over the long run and less than half the impact on GDP, as compared to raising income tax rates.

However, all three of these revenue options demonstrate that even with substantially higher tax revenues, debt-to-GDP would still continue to grow unsustainably—exceeding 200 percent of GDP by 2064—demonstrating that spending needs to be the primary focus to successfully reduce debt.

The Economic Effect of Tax Changes Matter for Reducing Debt-to-GDP

| Raise the Gas Tax by $0.35 | Eliminate the Exclusion for Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance | 28% CIT and 50% Top Individual Rate above $400K/$450K | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Long-Run GDP | -0.20% | -0.50% | -1.30% |

| Conventional Revenue, 2024-2033 (Billions) | $931 | $3,523 | $2,783 |

| Dynamic Revenue, 2024-2033 (Billions) | $797 | $3,117 | $2,116 |

| Dynamic Improvement in Debt-to-GDP Ratio, 2033 | 2.0 percentage points | 7.9 percentage points | 4.7 percentage points |

| Dynamic Improvement in Debt-to-GDP Ratio, 2064 | 5.2 percentage points | 21.3 percentage points | 10.2 percentage points |

Source: Tax Foundation General Equilibrium Model, September 2023.

That brings us to the options currently on the table. Unfortunately, President Biden’s plan to reduce the deficit, as described in his most recent budget, depends entirely on net revenue increases from raising economically damaging taxes—an approach inconsistent with successful efforts to reduce debt.[80]

The Biden administration’s estimates of nearly $3 trillion in deficit reduction under the budget are highly uncertain, particularly as they depend on a novel set of tax increases. On a conventional basis, Tax Foundation estimates the President’s budget plan would reduce the 10-year deficit by $2.5 trillion. Because the plan would reduce GDP by 1.3 percent, the deficit reduction drops to $1.9 trillion over 10 years on a dynamic basis.

By 2033, publicly held debt as a share of GDP will reach 115 percent under the baseline.[81] Pres. Biden’s budget would reduce it to 108.4 percent conventionally or 110.6 percent dynamically. In the long run (by 2064), the plan would reduce debt-to-GDP from 231.8 percent under the baseline to 207.0 percent conventionally or 214.6 percent dynamically.

The smaller improvement on a dynamic basis highlights the importance of minimizing the economic costs of tax hikes and instead seeking efficient sources of revenue.

For example, in contrast to Biden’s proposals, Tax Foundation’s Tax Reform Plan for Growth and Opportunity proposes replacing the current corporate income tax with a distributed profits tax and the current individual income tax with a much broader based flat tax, and reforming estate and capital gains taxes at death.[82] Base broadeners in the plan help offset the costs of the reforms, including eliminating most tax expenditures: the exclusion for employer-sponsored health insurance, all itemized deductions, and many tax credits.

The plan is approximately revenue neutral in the long run, and it raises about $522 billion over the 10-year budget window. Because it raises revenue more efficiently, it increases long-run GDP by 2.5 percent and reduces long-run debt-to-GDP by 9.2 percentage points on a dynamic basis to 222.6 percent.

In lieu of a fundamental overhaul of the tax system, lawmakers may consider permanence for all or part of the expiring Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) provisions. An across-the-board extension of the individual income tax expirations would be pro-growth but would significantly reduce revenue. Alternatively, lawmakers could build on the TCJA’s reforms to further broaden the base by, for example, using the options outlined in Tax Foundation’s Plan for Growth and Opportunity[83] and curtailing new green energy tax credits.[84]

Other reforms, such as permanent expensing for capital investments and R&D, would also enhance the efficiency of the tax system.[85] On a conventional and dynamic basis, such changes would reduce revenue in the short term, but, over the long run, the fading revenue cost and permanent economic benefit would be enough to slightly reduce deficits and the debt-to-GDP ratio.

Conclusion

Lifting the debt ceiling probably relieved some pressure on U.S. lawmakers to reduce the nation’s growing debt, at least until the debt ceiling returns in early 2025. Until then, other events are likely to remind lawmakers of the seriousness of the problem, including the recent downgrade of U.S. debt and the apparent doubling of the deficit over the last year. Now is the time for lawmakers to focus on long-term fiscal sustainability, as further delay will only make an eventual fiscal reckoning that much harder and more painful.

House Speaker McCarthy should follow through on his idea to convene a fiscal commission to deal with the long-term budgetary challenges facing the country. Any fiscal commission or other serious debt reduction effort must acknowledge the need to rein in the largest mandatory spending programs, Social Security and Medicare, which constitute a growing share of the budget and are the primary drivers of long-run deficits. The programs are unsustainable and are statutorily scheduled for a major reduction in benefits within the decade absent reforms.

Tax increases and tax reform should also be on the table. Lawmakers must not lose sight of the incentive effects of various possible reforms, both because of the demonstrable effects on the larger economy and standards of living, and because the effects in turn affect the sustainability of the debt reduction. Though it may not be politically popular to raise the gas tax or broaden the tax base, to the extent that a comprehensive deficit reduction package includes modest tax increases, such options are the most advisable on economic grounds. Ultimately, a better-designed tax system should be a goal of any fiscal consolidation package, noting that the majority of deficit savings should come from spending reforms.