The government can't keep up with its latest spending spree. Even though Democrats run Maine's government, it still finds ways to save money. Washington should pay attention to this.

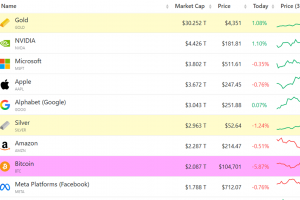

In addition to figuring out how much these bills will cost, the Congressional Budget Office has found that a number of executive orders, such as canceling college student debt, add nearly another $1 trillion to spending. This adds $4.8 trillion to the net deficit.

To make a bad situation even worse, there is now the $1.7 trillion Consolidated Appropriations Act omnibus, which includes $772.5 billion in nondefense discretionary spending through September 2023 and $858 billion in nondiscretionary defense spending.

The America First Policy Institute gave the top ten reasons to reject this omnibus in December 2022. There were three main points:

- The omnibus contains $15 billion in pork-barrel spending on over thirty-two hundred special lawmaker projects, which is swamp spending on steroids.

- Nondefense spending increases 9.3 percent from last year when the national debt is more than $31 trillion.

- The text of the omnibus is 4,155 pages long compared to the King James Bible of eleven hundred pages. Some members of Congress would be voting on this within two to three days.

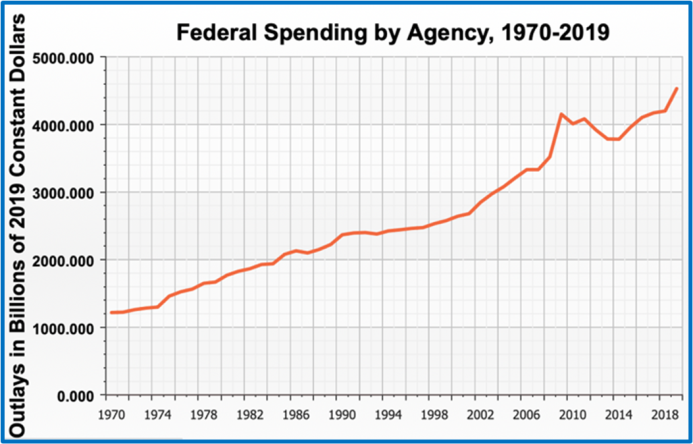

As the political Left has so often preached, especially in the 2020s, context matters. The minor context is that it personally took this author all 365 days of 2022 to read the New King James Bible cover to cover. The major context can be seen in the above chart (from Downsizing Government), which shows that since 1970, actual spending reductions, not just slower growth, are—to say the least—few and far between.

Government Spending Harms . . . Again and Again

In his book Power and Market, economist Murray Rothbard wrote,

There are fundamentally two ways of satisfying a person’s wants: (1) by production and voluntary exchange with others on the market and (2) by violent expropriation of the wealth of others. The first method [is] termed “the economic means” for the satisfaction of wants; the second method, the “political means.”

The former means is driven by Say’s law which, in short, is the economic reality that markets “produce in order to consume.” In similar fashion, the latter means is driven by the political reality that governments “spend in order to control.”

Greater government spending by its very nature, scale, and scope reduces the private sector by diminishing

- wealth on both Main Street and Wall Street, respectively by extracting ever more goods and services and by crowding out debt and equity;

- liberty through greater regulation, taxation, and inflation, which grants monopoly and cartel power to big government and woke capitalists, respectively; and

- morality as businesses increasingly seek political privilege and consumers seek welfare from the state.

Don’t Look to Washington for Inspiration; Look to Maine . . . Yes, Maine

The Maine Policy Institute recently published the Maine Policy Budget, a landmark report for the lobster state largely modeled and written by this author. This blueprint did two main things (no pun intended) in terms of spending:

- Provided a budget methodology (based on regulatory economics and objective statistics) not just for slowing spending growth but for reducing actual spending over a reasonable period of four financial years

- Delivered an actual budget, based on official data and simple formulas, that will produce budget surpluses (taxes minus spending) over the course of over four financial years

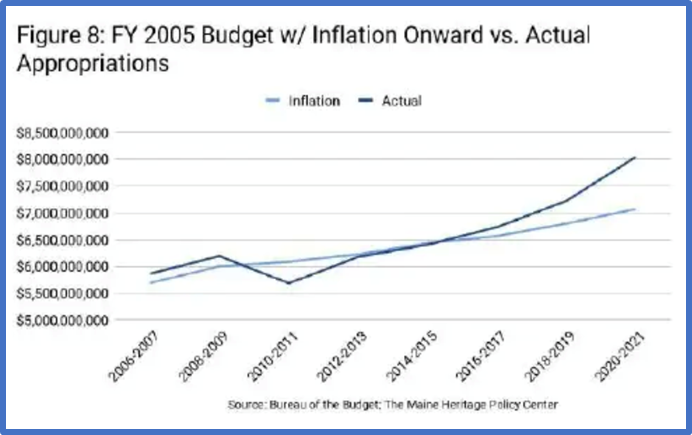

The 2019 Maine Policy Institute report entitled Cracking the Code provided the essence of the Maine state budget problem:

Figure 8 [below] shows the difference between actual government spending and spending based on inflation from the FY 2005 budget to present. The results show that the current proposal would be approximately $7.06 billion, a difference of $973 million, if the increases over previous budgets had not exceeded inflation. This would be more than enough to fill the Budget Stabilization Fund to its maximum capacity and still have a surplus available for subsequent budgets. In addition, state government would be able to reduce taxes or implement other significant reforms that could help all Mainers.

The "big three" of economic statistics are the CPI, the gross domestic product, and the unemployment rate. But, surprisingly, neither Maine nor any other U.S. state has an official CPI.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics does have CPI numbers for the Boston-Cambridge-Newton area, the New England states, the Northeast population centers with less than 2.5 million people, and the whole country. The Bureau of Economic Analysis gives the regional price parity and implicit regional price deflator, which are both based on the CPI.

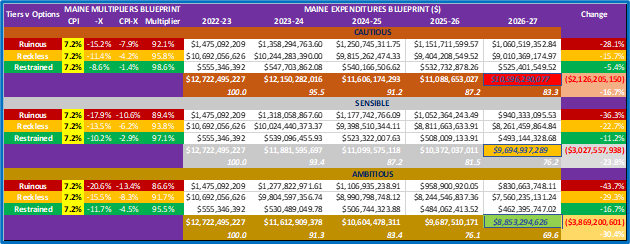

The data for these six metrics from 2016–17 to 2021–22 were put together and tested in Microsoft Excel using formulas for the maximum, average, and minimum. The result was that a CPI of 7.2% was expected. This number is also in line with what people think will happen with inflation and what modern monetary theory says.

Internal X-factor benchmarking was based on Maine's government agencies, which were broken up into 19 departments, 8 offices, and 6 independents. There were 33 umbrella agencies and 351 units. With a population of less than 1.4 million in 2020 (which, by the way, only grew by 2.6% from 2010 to 2020), that is a lot of red tape. The statistical maximum, median, and minimum were modeled in terms of four-year money materiality, four-year index change (I = 100), and one-year percentage change. This led to three umbrella-agency tiers: ruinous, reckless, and restrained. For instance, labor agencies are called "destructive," education agencies are called "reckless," and regulatory agencies are called "restrained."

For the four most recent financial years, external X-factor benchmarking was calculated the same way as internal benchmarking, but the nine Maine spending policies (for the 33 umbrellas) were mapped onto thirteen state spending policies from the US Census Bureau. The Census Bureau keeps track of how all fifty states spend their money, but only thirteen states, excluding Maine, were chosen. There were the New England six, the rural six, and the fiscal six (of two best, two mid, and two worst). Pennsylvania was a ruinous state, Rhode Island was reckless, and South Dakota was calm.

The possible X factors in CPI-X were based on the internal and external benchmarks taken together. Only the ones with restrained spending were used as real X factors to figure out the three spending options of being careful, being smart, and being ambitious. In a very similar way, the maximum, minimum, average, median, and the middle point between the average and median were all measured objectively. There was also use of the standard deviation.

This led to a set of CPI-X multipliers—cautious, sensible, and ambitious—for each of the three spending tiers of agencies (ruinous, reckless, and restrained), which led to three possible large spending cuts for each type of agency: 16.7%, 23.8%, and 30.4% over a four-year period.

If Maine Can Slash Spending, So Can Washington . . . and Sooner, Not Later

"Where there is a will, there is a way," as the saying goes. This year and next should show whether the US House of Representatives wants to cut federal spending. Nonetheless, the watershed Maine Policy Budget report has certainly provided a main way, or perhaps even the main way, to finally cut government spending.