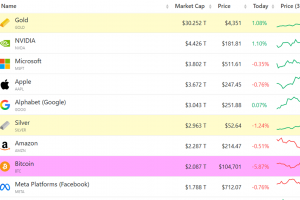

Long before there was the infamous German inflation of 1923, the Reichsbank created the scenario of monetary debasement.

One kilogram of gold (2.2 pounds) was worth 2,790 marks, and one mark was worth 358 milligrams. Their "gold" money, on the other hand, was worth different amounts in each country. The exchange rate for the pound sterling, for example, was 7.32 grams. The “gold” dollar had an exchange rate of 1.50 grams, meaning four gold marks exchanged for one US dollar.

But, like every other central bank, they wouldn't be honest, and the economy of the country would fall apart. Before and after World War I, Germany would take away people's gold, cause inflation, and change interest rates.

![The Reichsbank: Germany's Central Bank Lays Foundation of Monetary Disaster | Mises Wire]() Gold Confiscation

Gold Confiscation

Even though governments allowed a "gold standard" and personal use of gold, they did not hesitate to seize gold when they needed to raise prices to pay for things like war or welfare. With the signing of Executive Order 6102 on May 1, 1933, all US citizens were told to turn in their gold, whether it was in the form of coins, bullion, or certificates. Gold would be kept in vaults, and the U.S. would go off the gold standard by half. However, foreigners would still be able to use the dollar to buy gold.Since the people no longer had control over monetary policy, President Roosevelt would have no trouble making the money worth more. Before World War I, Germany's Reichsbank had the same advantages from confiscation. With tensions rising between the countries of Europe, the government would need more money to fight the war. Gerald Feldman in his book The Great Disorder states:

The Reichsbank viewed the dependency of coinage with increasing disapproval. As international tensions mounted in the prewar years, the Reichsbank also considered the excessive circulation of coinage dangerous, because it could act as an extreme brake on the Reichsbank ability to satisfy government liquidity requirements in the event of war.

The Reichsbankers knew there was going to be a war, so they took steps to reduce the number of gold coins in circulation and print more fiat paper notes to pay for the war. On June 18, 1914, Reichsbank President Rudolf Havenstein demanded that all banks send all of their gold to the Reichsbank vaults. This was ten days before Archduke Franz Ferdinand was killed in Sarajevo.

As always, the central bank printed more paper fiat notes then there was actual redeemable gold in the banking system. So, on July 31, 1914, the Reichsbank closed its doors to prevent bank runs until finally August 4, 1914, when the convertibility of the mark to gold was banned. Ludwig von Mises in his book Human Action (p. 472) states:

The inflationists are fighting the gold standard precisely because they consider these limits (bank runs, and no easy money) a serious obstacle to their plans. The governments were eager to destroy it, because they were committed to the fallacies that credit expansion is an appropriate means of lowering interest rates.

With gold no longer a problem, as gold premiums, deals, and exports of gold were made illegal, the Reichsbank was now free to expand money to finance the war.

Expansion of Easy Money in Germany

As we've already said, the central banks were known for making more paper money than gold. From 1908 to 1913, the number of high-denomination bills (those worth more than $50,000) went from 1,951,000 to 2,574,000. The number of five- and ten-dollar bills went up from 62 million to 148 million.By 1914, there were 2.1 billion marks in circulation. By the end of the war in 1918, there were 22.2 billion marks in circulation. Prices will always go up when there is inflation. Printing paper money will make the currency worth less, and businesses will have to adapt to these changes. The German government did this during World War I.

Food prices were kept very low, but there were huge shortages of all kinds of goods. In 1918, the German Board of Public Health said that "763,000 Germans had died of disease and starvation because of a blockade."

Was there a wall? Or did bad economic policy before and during the war cause it? The prices of goods were kept low by price controls, and the German stock market was closed until December 1917, which made things even worse. Lacks of food were also caused by conscription in rural Germany and the movement of farm hands to factories that made weapons. Either way, farmers cut their production because there were no price incentives to do so. Frederick Taylor’s The Downfall of Money speaks on this:

It was clear that Germany was turning into two countries: an urban Germany, dependent on food imported from abroad or the countryside; and a rural Germany, which was self-sufficient and reluctant to release what it grew or reared unless the price was right. This division will continue well into the unhappy peace.

Not only did the central bankers and politicians ruin the economy of Germany, but they also successfully divided the people against each other.

Conclusion

The mistakes made by the German government's central bankers and commissars would follow the German people into the uneasy peace of the Weimar Republic, and as we now know, things were only going to get worse. Both the new Weimar Republic and Nazi Germany would keep the ideas of easy money, price controls, and making war look like a good thing. The years of government interference had made the German people, in Thomas Mann's words, “Cold hearted and reliant on politics and destiny and forgetting on how to rely on themselves as individuals.”

But many people in Europe and abroad have not learned the lessons of government control. The bankers and politicians, however, have learned. But they did not learn basic economics. They learned how much they can get away with.

Gold Confiscation

Gold Confiscation